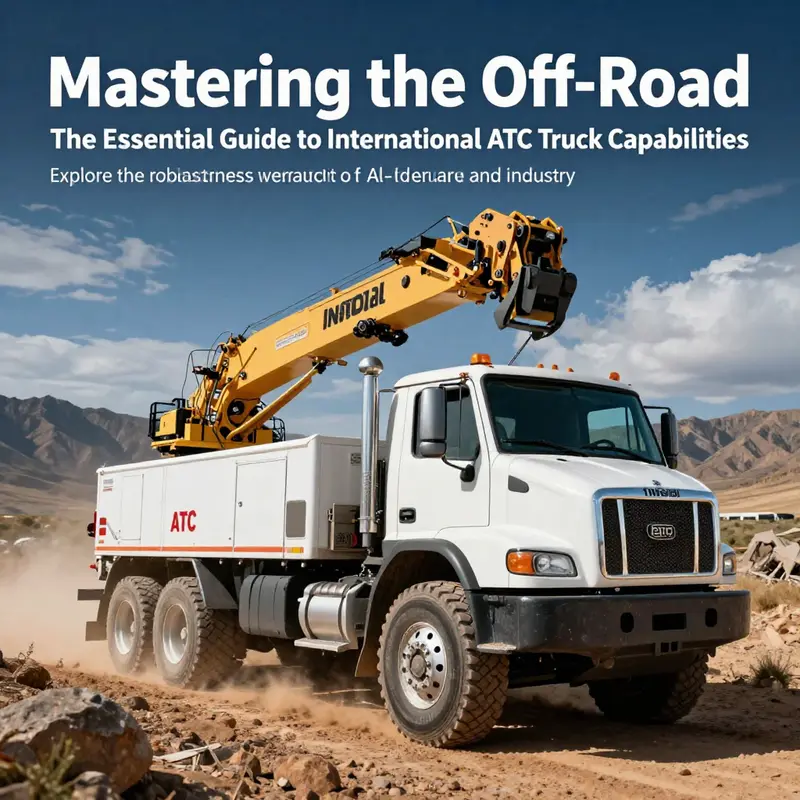

The allure of off-roading is irresistible for adventurers, rural dwellers, and racing enthusiasts alike. All-Terrain Crane Trucks (ATC) represent the pinnacle of heavy-duty vehicles, engineered for unfathomable terrains and extreme environments. This guide will delve into the essence of what ‘off-road’ truly means for these trucks, examining their impressive mobility across diverse terrains, the technical features that enhance their performance, and their applications in harsh environments. Join us as we uncover the world of ATC trucks, empowering your off-road explorations and industrial endeavors.

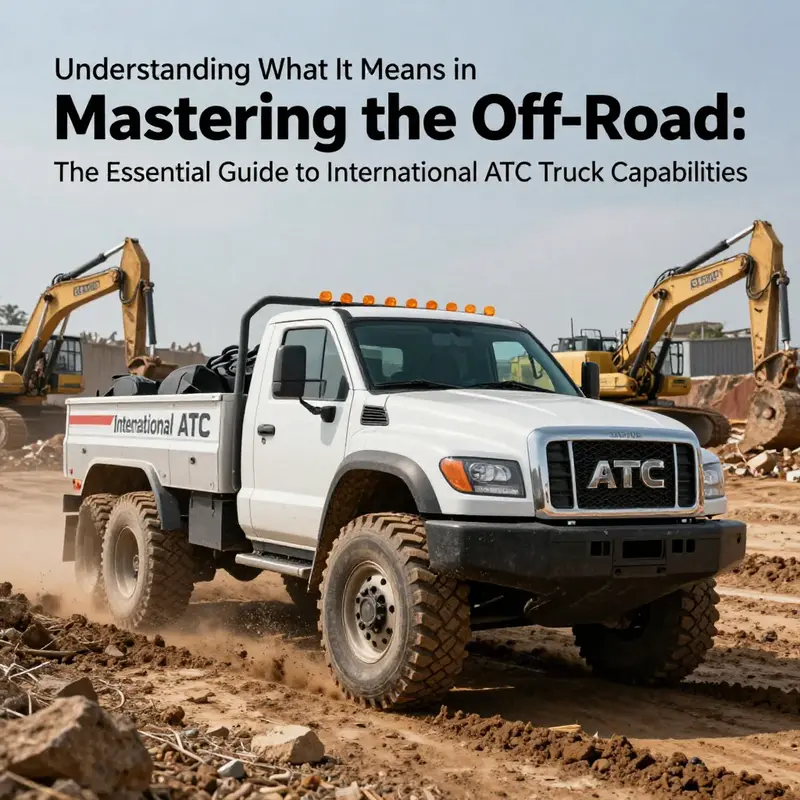

Off-Road ATC Mobility in International Heavy Trucks

In international heavy hauling, off road capability with automatic traction control ATC is more than a feature set, it is a design philosophy. It signals a machine built to survive and perform where paved roads end. When applied to all terrain crane trucks and other specialized platforms, ATC weaves together mechanical robustness with electronic intelligence to create a predictable, controllable lift in challenging terrain. Off road here means sustained grip, stability, and controlled crane behavior as the ground shifts beneath the tires. It is a language of torque and traction spoken through a blend of rugged hardware and adaptive software.

To harvest these capabilities, engineers emphasize ground clearance, suspension, and drive configuration. A heavy duty chassis must tolerate scrapes and undulations without bottoming out. High ground clearance protects drivetrain and payload stability when negotiating ruts or rocky approaches. The suspension is about how the vehicle negotiates constant up and down motion; robust leaf springs or air suspensions absorb shocks and maintain tire contact across surfaces. This contact is essential for traction and for controlling the crane dynamics when lift loads are high and the center of gravity shifts.

Drive configuration matters. All wheel drive or four wheel drive or six wheel configurations maximize grip as surface conditions change. A low range transfer case provides torque at low speeds for cautious progress. Differential locks augment traction by preventing wheel slip. When tuned with braking and steering, these features give the predictability needed to operate a heavy lift on rough ground.

ATC threads through both mechanical and electronic layers. ATC systems automatically distribute power, modulate brake intervention, and mitigate wheel spin as conditions become unpredictable. The goal is to keep the vehicle moving in a controlled safe manner while maintaining crane readiness. The ATC networks rely on wheel speed sensors, steering angle, gyroscopic data, and terrain feedback to decide when to restrain or rebalance torque. In articulated off road configurations, ATC helps manage load transfer as the crane extends and the chassis twists over uneven surfaces.

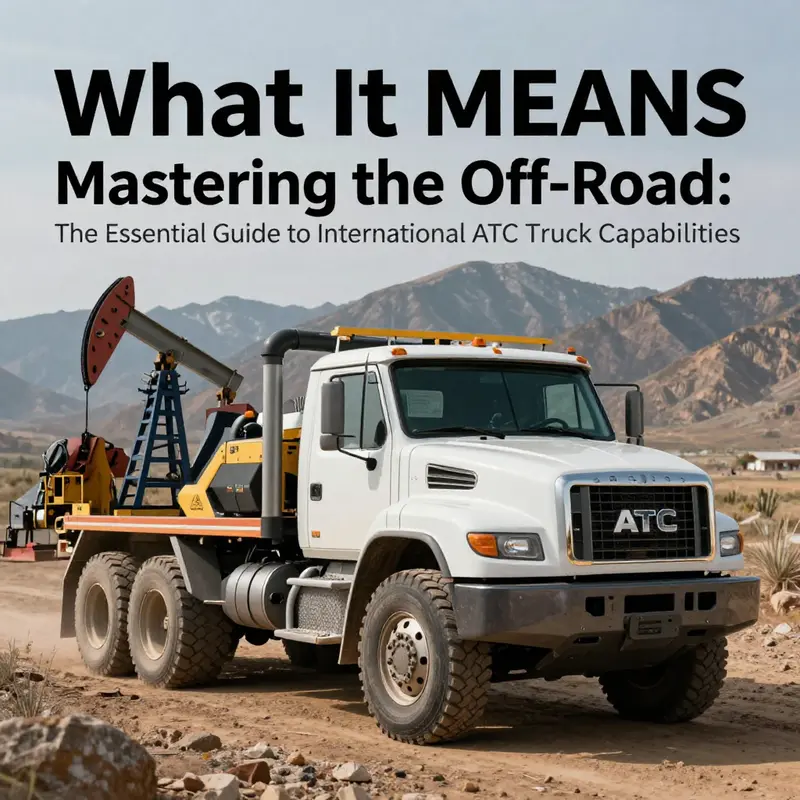

Practical deployments. Off road ATCs operate in remote mining sites, oil and gas exploration zones, disaster relief operations, and rugged infrastructure projects. They are not just transports but mobile lifting platforms that guarantee stability and crew safety under harsh conditions. The integration of robust mechanical design with sophisticated stability systems yields a platform able to lift heavy loads on uneven ground, set up a crane in confined spaces, and adjust to ground conditions that could otherwise compromise balance.

The electronic safety and stability architecture reflects risk management. Electronic stability programs ESP tuned for off road use work with traction control systems to monitor wheel slip, yaw, and tilt tendencies. Software translates sensor data into adjustments such as engine torque changes, targeted braking, and reweighting power to maintain grip. Terrain specific driving modes muddy, sandy, rocky, or snowy optimize engine mapping, transmission response, and braking to match surface conditions. The objective is not to eliminate risk but to manage it with proactive sensing and adaptive control.

The value of off road ATC is not only navigation but reliability. In remote mining or disaster relief, the vehicle can access lifting points and reposition the crane as sites evolve. The integration of data driven control enables smoother lifts and safer placements. Real time sensor fusion informs operator decisions and coordinates with the crane operation to keep the load path stable as ground moves.

Maintenance and lifecycle. Off road ATCs endure higher stresses than highway trucks. Routine maintenance of chassis components, driveline, suspension, and hydraulic crane systems is essential. Route planning and operator training aligned to the intended envelope reduce wear. Ongoing calibration of ATC and ESP ensures safe responses as tires wear and terrain conditions change.

In summary, off road capability in international ATCs is a system of features that together expand the operational envelope. It blends heavy duty mechanicals with electronic stability and real time control to enable lifting and transport in remote environments. It is a pathway to extending reach to places where the pavement ends and opportunity begins.

Rugged Power, Unseen Mechanics: Off‑Road Mastery in an All‑Terrain Crane Truck

Across remote worksites where asphalt ends and the land remembers every season, the all‑terrain crane truck stands as a synthesis of brute capability and careful engineering. The phrase off‑road, when attached to such a machine, is not a mere descriptor of a higher ground clearance or a larger tire. It signals a holistic design philosophy aimed at keeping a crane and its operator moving when the terrain itself seems designed to resist movement. In practice, off‑road capability for an all‑terrain crane truck means more than being able to traverse a dirt road; it means delivering controlled power, reliable traction, and predictable handling from the moment the tires bite into mud or snow until the crane lowers its hook on a distant, rugged job site. The chapter that follows navigates the terrain of this capability—how an off‑road ATC truck achieves its reputation through a suite of interlocking systems, how those systems interact under the stress of real work, and how operators train their senses to work in harmony with the vehicle’s robust, sometimes quiet, intelligence.

To begin, the core idea of off‑road in this class of vehicle is mobility itself. An ATC truck is built to move across surfaces that would confuse or immobilize a standard highway tractor. The unpaved world—mud that clings to tires, sand that shifts like a living thing, gravel and rock that threaten a bonnet and a cab, snow that can float a truck on its own, and uneven ground that yaws the chassis—demands a fundamental rethinking of what safety and performance look like. Where a highway pull might hinge on aerodynamic drag and highway gearing, off‑road performance hinges on a set of mutually reinforcing geometries and control loops designed to keep the vehicle stable, the load secure, and the crew safe.

A practical way to frame what this means is to imagine the truck as a moving anchor point for heavy lifting in places where ground and weather conspire to complicate every operation. In mud, the vehicle cannot merely rely on a clean torque curve; it must distribute torque in a way that preserves traction at each wheel. On rock, the chassis must clear enough to avoid bottoming out while also absorbing jolts that would rattle the crane’s joints and potentially unsettle a long, rotating tower. In sand, one must temper power and weight transfer so that a wheel does not simply sink, and in snow, grip must be maintained while steering remains predictable and responsive. The off‑road ATC truck is engineered to perform under all those conditions by marrying a robust mechanical backbone with a responsive electronic brain that can interpret terrain in real time and translate that interpretation into purposeful action.

The mechanical backbone starts with the obvious, yet essential, features: high ground clearance, an intentionally reinforced undercarriage, and rugged chassis construction. Ground clearance is not a cosmetic number; it is the difference between a skidded oil pan and a successful pass over a rock or a rut that hides a sharp obstacle. A sturdy chassis, in turn, supports a suspension system capable of absorbing, rather than transmitting, the shocks of irregular terrain. The suspension is typically heavy‑duty in design, with options that range from solid axle configurations to more advanced independent suspensions, all chosen to maximize wheel contact with the ground across varying surfaces. When the terrain tilts and shifts, the suspension keeps the tires in contact with the ground just long enough for the traction system to make a decision about power distribution, and it damps the oscillations that would otherwise fatigue the operator and fatigue the crane’s structural elements.

Traction is the heartbeat of off‑road capability. Advanced driveline configurations—whether four‑wheel drive or all‑wheel drive, sometimes in a six‑wheel format—are complemented by a low‑range transfer case that allows for maximum torque at very low speeds. In practice, this means a crane truck can pull heavy, awkward loads up a slope or move over loose ground without the tires spinning away or the engine stalling into a high‑rpm panic. Differential locks, often both mechanical and electronically controlled, are the brakes for wheel slip. They force equalized torque to wheels with grip, preventing one tire from spinning uselessly while the others sit idle. In the field, those modes are not flashy features; they are the difference between a safe, stable lift and a mission abort when a critical lift must happen on uneven terrain.

But the wheels and their grip tell only part of the story. The engine and transmission deserve equal attention because their behavior in off‑road conditions is a study in disciplined torque management. Heavy‑duty diesel engines deliver high torque at low speeds, a necessary trait when a crane must move a heavy load across a washboard patch of earth or up a ridge where momentum is unreliable. The transmission’s role is to translate that torque into controllable movement, modulating gear ratios to keep the truck in the sweet spot of the engine’s curve. In off‑road operations, this often means staying out of peak torque bands that would overwhelm traction and cause wheel spin, and instead sustaining steady torque delivery that the tires can transform into forward progress. The result is a vehicle that feels quiet, purposeful, and almost surgical in its decision to step or remain still at a user’s command.

A modern off‑road ATC truck does not rely on raw horsepower alone. It depends on an integrated set of electronic stability and traction systems designed to work on loose or uneven surfaces. An electronic stability program adapted for off‑road use helps prevent the kind of oversteer or roll that can occur when a crane is extending a jib or winching near the edge of a slope. Traction control systems monitor wheel slip and modulate engine output or brake force to maintain grip. These systems are not about replacing driver judgment; they are about extending it—giving operators a window into how the vehicle interprets the terrain and how the vehicle will respond to their input. In combination, these control loops create an operating envelope that a driver can trust, even in conditions that might initially feel uncertain or unpredictable.

Safety in off‑road operations extends beyond stability and traction. Rollover protection systems and reinforced chassis frameworks are built into the vehicle from the ground up for the hazards of rugged environments. The presence of roped or reinforced structures around the cab, along with energy‑absorbing crush zones and properly positioned tie‑offs for loads and stabilizers, ensures that the operator and crew have a margin of safety when the terrain decides to test the rig’s limits. The crane itself benefits from the same emphasis on safety via structural integrity. A crane that is stable on a flat surface can become overstressed on a slope if the base vehicle lacks the proper countermeasures to manage lateral forces. Terrain‑adaptive driving modes that adjust engine torque, braking bias, transmission logic, and even the feel of the steering become essential tools for the operator at the moment when a crane must reach out over uneven ground to lift a heavy object or hold a load steady during a remote installation.

The role of terrain adaptation cannot be overstated. A single feature, such as a specialized drive mode for mud or rock, acts as a selector that tunes several subsystems in a coordinated manner. The engine’s torque curve is reshaped to reduce sudden spikes in power that could break traction. The transmission shifts are softened to prevent wheel hop, while the braking system is tuned to preserve steering feel even as the vehicle slows under load. Terrain modes also influence brake engagement at the wheels, a subtle but powerful way to preserve stability at the contact patches. The result is a machine that does not merely survive on rough ground; it behaves with a measured confidence that allows an operator to plan, execute a lift, and undo a set of stabilizers without second‑guessing the machine’s reactions.

Maintaining and operating such a vehicle requires more than mechanical know‑how; it calls for a cultivated sensibility about surface conditions and load dynamics. A driver of an off‑road ATC truck develops a mental map of how the terrain will respond as the machine moves. What starts as a simple climb can quickly become a controlled negotiation of ruts and slabs; what begins as a routine lift may require a repositioning of the crane to maintain balance as the ground shifts beneath the outriggers. In these moments, the operator’s experience with wheel placement, weight distribution, and the timing of hydraulic actions blends with the vehicle’s internal logic. The operator becomes a living interface with a machine that is, in effect, a delicate balance between inertia and control. The crane, trained to follow a programmed sequence, relies on the truck’s ability to hold its ground and provide steady support as loads shift and reposition. The broader lesson is that off‑road capability is not a single gadget but a system of interdependent competencies—mechanical power, traction, stability, and controlled automation—that together form a resilient enterprise on tough terrain.

This integrated approach also shapes how work is planned on remote sites. Operations teams must understand the limits and strengths of their equipment, planning lifts, drags, and placements in a way that honors the terrain’s constraints. The presence of high ground clearance, durable suspenders, locked differentials, and terrain‑specific modes encourages a more granular planning approach. It invites crews to think about where stabilizers will be deployed, how the truck will be positioned to minimize the need for long winching lines, and where the crane will reach to avoid ground disturbance that could threaten footing. The planning mindset evolves from simply getting from point A to point B to orchestrating a coordinated sequence of movements that respects both the load’s stability and the ground’s capacity to bear it. In practice, this means documenting the surface, evaluating the width of turns, estimating the soil’s bearing strength, and anticipating how the ground might respond to the weight and movement of the outriggers and the crane. The outcome is not just a job done; it is a job done with a measured, repeatable discipline that reduces risk and improves consistency across crews and sites.

The off‑road capability of a crane truck thus becomes a narrative of reliability. Reliability is not about the absence of challenge; it is about predictable performance under pressure. When the going gets tough—whether it is mud that clutches the tires, a steep approach with poor visibility, or a surface that offers variable traction—the vehicle’s design returns steady feedback to the operator. That feedback, in turn, translates into actions—precise throttle inputs, careful brake modulation, steering corrections, and measured crane movements. The operator’s hands become the interface that translates the machine’s robust subsystems into practical outcomes: a lift performed with confidence, a set of stabilizers deployed with poise, a crane extended and retracted with a sense of balance that keeps both the load and the truck secure.

Yet off‑road capability is not a license to ignore the physics of the surface or the fatigue of the operator. It requires ongoing maintenance and attention to the wear patterns that come with non‑paved work. Tires, for instance, bear the brunt of uneven terrain and must be selected, inflated, and rotated with mind to terrain type and load. The suspension’s bushings and linkages wear differently when absorbing the constant shocks of uneven ground, and the drivetrain’s seals, lubricants, and heat management systems must be monitored for signs of stress. The chassis should be inspected for cracks or deformities that a rough surface might reveal only after a long haul. The crane’s hydraulic systems require clean lines, stable temperatures, and secure outriggers so that operations remain precise even as the ground shifts. In short, off‑road capability is a promise that materializes only through a culture of maintenance, training, and disciplined use. The truck’s systems are robust, but their longevity and usefulness depend on how well they are cared for and how thoughtfully operators use them on the ground.

In the broader arc of heavy equipment operation, the off‑road ATC truck represents a bridge between mobility and precision. It links the necessity of moving bulky, heavy loads across challenging terrain with the discipline of performing lifts with a crane that must remain stable. The off‑road capability multiplies a site’s potential, unlocking workflows that would be impossible with conventional road‑bound equipment. It makes possible the kind of remote project logistics that define modern infrastructure, energy, and resource development—the things that often require teams to reach beyond paved routes and into the heart of rugged environments. The value is measured not just in the number of meters of ground covered, but in the reliability of every action the truck enables—every lift, every stabilizer placement, every rotation of the crane, and every safe return to base. In this sense, off‑road capability is the quiet force behind loud, consequential work on the planet’s most demanding sites.

For readers who want a deeper dive into the engine side of resilience—a subject that anchors many off‑road behaviors—the path to understanding runs through the basics of diesel power, torque dynamics, and the ways that modern drivers and machines coordinate to keep a heavy system in balance. A concise route to that knowledge can be found in the accessible guide on diesel mechanics, which traces the essential steps from piston movement to fuel delivery and heat management. This resource, while not a replacement for formal training, complements the experience of operating an off‑road ATC truck by offering a clearer picture of how a hard‑working engine behaves under load and over varied terrain. It is about recognizing that the quiet, relentless torque that pushes a heavy crane through rough ground comes from a network of components that must be harmonized through design, maintenance, and practice. And the more a driver understands that harmony—the more the operator grasps the relationship between engine torque, transmission behavior, wheel traction, and suspension response—the more capable the whole system becomes when Field conditions demand precise, deliberate action.

As this exploration makes clear, the off‑road capability of an all‑terrain crane truck is not a single feature but a constellation of design choices, control strategies, and human skills that work together. It is a performance‑oriented philosophy embedded in the vehicle—from its ground clearance and chassis protection to its differential strategy, from its terrain modes to its stability logic, and from its high‑torque engine to its fatigue‑aware maintenance regime. The result is a machine that can meet the most demanding demands of rugged sites while keeping operators safe, loads secure, and work progressing toward completion. In the end, off‑road capability is about trust—the trust built by the vehicle in the field and the trust the operator places in the vehicle. When the terrain tests the limits, the all‑terrain crane truck does not fail its test; it adapts, responds, and continues the job with a quiet but undeniable authority. That is the essence of what off‑road means in this context: a durable, intelligent, and disciplined partner that makes the most unforgiving terrain a place where work can be done, and done well.

Internal link for deeper engine insight: mastering-diesel-mechanics-your-step-by-step-path-to-success

External resource for official specifications and guidance: For a canonical reference on heavy‑duty truck design principles and official manufacturer guidelines, see the external resource on the topic at the following site: https://www.internationaltrucks.com/

Rugged Routes, Robotic Resolve: Interpreting Off-Road Capabilities in International ATC Tractors for Harsh Environments

Off-road, in the context of an international All-Terrain Crane Truck (ATC) or similar heavy-duty platform, is not a mere adjective for rougher pavement. It is a defined capability—an engineering synthesis that lets a vehicle operate reliably on surfaces that test traction, stability, and payload management to their extremes. When the terrain turns from smooth to unpredictable, the vehicle must maintain control, protect its lifting functions, and sustain a predictable work rhythm. In this sense, off-road becomes a performance envelope rather than a simply expanded speed range. The modern ATC-equipped truck that is built for international work sits at the intersection of rugged mechanics and intelligent control, where physical robustness and adaptive software work in tandem to translate raw terrain into steady, controllable movement and safe crane operation even under load. The result is a vehicle that can reach remote sites, descend into trenches, or traverse uneven construction zones without surrendering uptime or safety.

To understand what off-road means for an international ATC in practice, one must start with the core mechanical design choices. The chassis fight to stay level and resist bottoming out as uneven ground tries to force the undercarriage into unexpected contact with obstacles. Therefore, high ground clearance becomes a standard, not a luxury. It is paired with a suspension system engineered to absorb the thumps and jolts of rocky or rutted paths. Heavy-duty configurations, whether based on reinforced leaf springs or air-suspension modules, are chosen to maintain wheel contact and to preserve stability when the crane needs a precise stance for lifting or when a heavy payload shifts during traverses. The drivetrain follows suit with all-wheel drive or even multi-axle configurations such as 6×6, which offer additive traction on surfaces with low friction, such as wet mud or loose sand. A low-range transfer case is essential; it provides torque at very low speeds, enabling controlled climbs or careful extraction from soft substrates where momentum would only dig the tires deeper. Differential locks—either mechanical or electronically actuated—become a practical necessity because any loss of traction can quickly translate into unstable steering or reduced lifting accuracy under load. In the harshest environments, these mechanical features are not luxuries but safeguards that sustain mobility without compromising the crane’s positional integrity.

Beyond the raw chassis and driveline hardware, off-road capability for international ATCs is increasingly defined by adaptive software and integrated sensing. Terrain-specific driving modes—mud, sand, rock, snow, and similar profiles—adjust engine torque, transmission behavior, traction control thresholds, and braking dynamics to match surface conditions. Electronic Stability Programs (ESP), recalibrated for off-road contexts, help constrain yaw and roll tendencies when the vehicle is driven over uneven surfaces at low speed or while carrying heavy lift configurations. Traction Control Systems (TCS) monitor wheel slip, dynamically redistributing power to maximize grip where it is available and soft-paltering when traction is scarce. These controls are the non-physical part of off-road capability; they translate the physical advantages of ground clearance and locked differentials into predictable, safe handling.

Perception and safety technologies have become as important as the mechanicals themselves. Rollover Protection Systems (ROPS) and reinforced chassis structures provide a safety envelope for crews in demanding environments where sudden shifts in center of gravity are possible during lifting operations on uneven ground. The perception suite—comprising cameras, lidars, radars, and multisensor fusion algorithms—must contend with dust, heat, vibration, and the absence of reliable network links. In the field, a sensor that is abruptly degraded by dust or temperature swings can undermine the entire automation loop, eroding trust in the off-road capabilities. It is here that robust sensor design and resilient software architectures matter as much as the physical chassis. The aim is to keep the perception and control chain nested within tolerances even when conditions threaten to pull it apart. The driving experience in such environments becomes a balance between confident, steady vehicle dynamics and the crane’s precise control, ensuring that lifting operations remain within safe envelopes while the vehicle negotiates rough terrain.

Off-road capability also implies a deliberate limitation: these machines are not tuned for long, high-speed highway cruising. The same rugged features that enable performance off-road—heavy suspension stiffness, locked differentials, and torque-rich low-speed operation—translate into higher fuel consumption on pavement and increased wear when run in road-friendly configurations. The engineering trade-off is clear. A vehicle that excels on a remote, unpaved worksite should not be treated as a dedicated highway transporter. The very design choices that maximize traction and clearance can degrade ride quality, steering feel, and tire wear when the vehicle is compelled to spend long durations on tarmac. In practical terms, operators plan routes and task sequences that leverage off-road capabilities where needed while reserving highway stretches for re-positioning rather than continuous travel.

A more nuanced understanding of off-road performance comes from examining automated trucking systems that extend beyond manual control. Automated Truck Control (ATC) systems, designed to manage complex driving tasks in demanding conditions, have emerged as a meaningful upgrade in international contexts where remote operations, limited infrastructure, or hazardous environments demand higher uptime and safety. These systems must handle the same physical challenges as a human driver—steering, throttle, braking, and gear selection—while also managing more complex tasks: dynamic traction distribution, cooperative braking with trailers, and the precise coordination required to lift or lower heavy loads in uneven surroundings. In off-road settings, automated traction control becomes especially critical for articulated configurations, where helical dynamics and trailer yaw can amplify instability if wheel slip occurs at the articulation point or on one side of the steer axle. The ability to automatically lock or unlock differentials in response to slip, and to modulate power distribution across axles, can dramatically improve mobility and control where surface friction is uncertain.

This is where research in automated traction control offers practical insight. Studies highlighted in arXiv.org (2021) emphasize the importance of adaptive differential management for articulated vehicles in off-road contexts. Rather than a binary locked-or-unlocked approach, modern solutions dynamically decide when to engage or release locks based on real-time data about wheel slip, traction coefficients, and load distribution. Such approaches can maximize grip and maintain directional stability as the vehicle negotiates rutted paths, shallow mud, or soft sand. In real-world operations, these automatic control strategies translate into measurable benefits: fewer recoveries from immobilization, higher uptime, and more predictable crane positioning during lifts undertaken on uneven ground. They also underscore a broader design principle: automation in off-road ATCs must integrate tightly with the physical system—it’s not enough to have clever software if the mechanical platform cannot provide consistent traction or if the sensing is unreliable.

The deployment of automated off-road trucks in harsh environments has moved beyond proof-of-concept into the realm of practical, field-ready capability. Industry deployments—whether in remote mining zones, oil and gas exploration fronts, or disaster-relief corridors carved through rugged terrain—illustrate both the promise and the pitfalls of automation in demanding settings. On one hand, automated systems can maintain a steady work cadence under heat and dust, reducing operator fatigue and enabling longer, safer shifts for heavy lifting and material movement. On the other hand, real-world operations reveal vulnerabilities that must be addressed before fully autonomous operation becomes routine in extreme environments. Sensor degradation from dust or particulate matter, temperature extremes that stress calibration, and the risk of communication delays or disruptions in remote areas can erode the reliability of centralized control or fleet coordination. These lessons emphasize the need for robust, redundant sensing architectures, fault-tolerant software, and adaptive control strategies that gracefully handle degraded information or intermittent connectivity. They also highlight the value of operational protocols that combine automation with human oversight in transitional modes to preserve safety and performance during contingencies.

To validate and refine these capabilities, automotive proving grounds have become essential. Modern proving sites, including those cataloged in Dewesoft’s updated 2025 list, simulate extreme off-road scenarios far beyond what any public road can offer. Desert dunes test traction and heat management; Arctic facilities probe cold-start behavior, hydraulic performance in low temperatures, and the resilience of electronic systems to frost; mountainous tracks assess stiffness and control authority on steep grades with variable surface friction. These controlled-but-demanding environments enable engineers to push ATC systems through comprehensive test matrices, isolating specific failure modes and verifying that the control algorithms respond appropriately under a spectrum of surface conditions and ambient stresses. The practical upshot is a more reliable transition from lab to field, where the unpredictability of real sites remains the ultimate test.

In contemplating what the off-road capability means for an international ATC-equipped truck, it is helpful to consider the broader spectrum of lessons learned from industrial applications of automated trucks. The central message is not simply that automation reduces human effort; it is that reliable performance in harsh settings depends on a tightly coupled system of robust mechanics, smart control, and resilient perception. Vehicles must negotiate rough terrain, manage traction with finesse, and maintain lift accuracy even when ground conditions threaten to derail the operation. This triad—physical ruggedness, advanced traction and stability control, and dependable sensing—becomes the backbone of a credible off-road ATC capability. When all three strands align, a site that would once require multiple trips and risky manual maneuvering can become a contiguous workfront where lifting, placement, and material handling proceed with consistent tempo.

The practical implications for operators and engineers alike are meaningful. In remote industrial operations, time is money, and the ability to stay productive in the face of surface uncertainty directly translates to fewer delays, safer lift operations, and improved crew welfare. The automated traction control work, when done well, reduces the cognitive load on the human operator and makes the machinery more forgiving in the early stages of automation adoption. Yet there is no magic wand. The system must be designed with failure modes in mind. Redundant sensors, fail-safe control loops, and clearly defined transition pathways between autonomous and manual control can spell the difference between a smooth mission and a costly standstill. In practice, this means investing in sensor robustness, testing across a representative range of harsh environments, and building software architectures that can tolerate partial system degradation without catastrophic performance loss. It also means recognizing that off-road capability requires ongoing adaptation as terrain, climate, and payload demands evolve.

Within this landscape, the maintenance and upkeep of an off-road capable ATC are themselves part of the capability equation. Operators emphasize routine checks of ground clearance, suspension travel, and the integrity of the locking mechanisms that ensure traction is available when needed. The perception system, which underpins the safety and control logic, must be regularly tested against dust ingress, thermal drift, and vibration, with calibration routines that can be executed in field conditions. The integration of diesel, hydraulic, and electrical subsystems is another area where attention pays off in reliability; a well-tuned powertrain with a stable hydraulic circuit reduces the likelihood that a heavy-lift operation is disrupted by a minor mechanical anomaly. For technicians and operators, the practical takeaway is straightforward: treat the off-road ATC as a dynamic system that requires both regular preventive maintenance and adaptive operational planning. The vehicle is designed to perform in adverse settings, but its performance hinges on disciplined upkeep and a clear understanding of the terrain-to-task relationship.

As the conversation about off-road capability deepens, an important thread concerns how technicians and operators gain confidence in automated systems while honoring the realities of rugged work sites. The chapter of the technology story that follows automation is not merely about smarter hardware; it is about a human-machine collaboration that respects the constraints of the environment. Operators learn to interpret automated cues, trust the traction control decisions under slow, deliberate maneuvers, and maintain a readiness to intervene when the terrain presents an unanticipated hazard. The crane’s safety systems, including their interaction with vehicle dynamics, must be tuned to ensure that lifting operations stay within safe envelopes even as the vehicle negotiates unpredictable ground. In this sense, off-road capability becomes a shared practice—an emergent capability born from the fusion of sturdy hardware, sophisticated control logic, and the daily, on-site experiences of crews who know that a rough jobsite demands both discipline and adaptability.

For practitioners seeking pragmatic guidance, maintenance and operation protocols that support off-road ATC performance can be thought of as an ecosystem. The chassis and driveline components provide the foundational stability and traction, while the ATC control layer adds the intelligence that maintains ground contact and keeps the crane’s geometry stable during lifts. The perception layer supplies the situational awareness necessary for safe operation, and the safety stack—ROPS, reinforced structure, and robust emergency procedures—constitutes the last line of defense if terrain or sensor anomalies threaten safe operation. Across this ecosystem, the objective remains consistent: to complete the task at hand with minimal downtime and maximal safety, even when the site presents the most adverse conditions.

In sum, off-road in an international ATC context is a holistic capability. It encompasses the physical design required to traverse rough terrain, the mechanical systems that distribute power and maintain wheel contact, the electronic controls that keep vehicle dynamics in check, and the perception and safety architectures that ensure lifting operations remain precise and secure. It is a capability that grows through iterative testing, field deployment, and continuous learning from industrial experiences in harsh environments. When viewed through this lens, off-road becomes not just a feature set but a performance discipline—one that enables international work across remote, rugged landscapes while sustaining the high standards of safety, reliability, and operational tempo that the task demands. The road ahead for ATC systems in off-road contexts will likely hinge on further advances in robust sensor fusion, resilient communication under constraint, and adaptive controls that can learn from on-site feedback without compromising safety. As these developments mature, the image of the off-road ATC will be less about a vehicle braving the wilderness and more about a coordinated, trustworthy system that integrates mechanical durability, intelligent control, and human expertise to meet the demands of the world’s most challenging work sites.

External reading: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352940725000128

Final thoughts

In the world of international All-Terrain Crane Trucks (ATC), ‘off-road’ embodies a multifaceted concept that extends beyond mere capability. It signifies an extraordinary union of engineering precision, mobility, and resilient performance, tailored to face the most daunting challenges of terrain and environment. The insights shared here not only illuminate the rugged prowess of ATC trucks but also serve as a guiding beacon for enthusiasts, racers, and landowners. Embrace the adventure and utility that these remarkable machines offer, and venture further than ever before with the right tools for the journey.