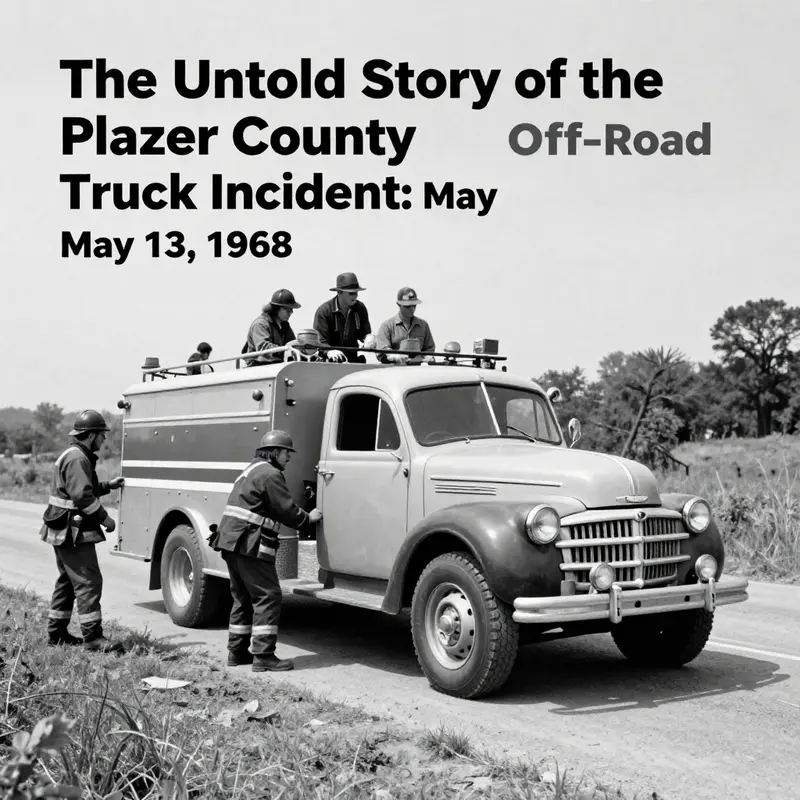

On May 13, 1968, an incident in Placer County involving a truck veering off road into a river has sparked curiosity and speculation among off-road enthusiasts. Despite extensive research, concrete evidence of this event remains elusive. However, the discussion it generated sheds light on critical aspects of off-road vehicle safety, the impact of environmental conditions on driving, and how such incidents were handled by emergency responders at the time. As we delve into these chapters, we will uncover discrepancies surrounding the supposed incident, investigate safety regulations that governed off-road vehicles back then, explore weather’s influence on road safety, and review emergency response actions taken during that era. Each element contributes to a richer understanding of vehicle safety in the rugged terrains of Placer County.

On May 13, 1968: Reconsidering the Placer County Truck Incident

The May 13, 1968 Placer County truck incident remains a compelling memory for some communities. This chapter does not declare the event true or false; it uses it as a case study in how memory travels and how historians test claims against the record. The central question is what counts as solid evidence when the public record is silent. The absence of a published accident record tied to that date is not proof that no incident happened, but it is a strong cue that memory may be outpacing documentation.

A practical method begins with locating official records: accident logs, CHP incident data, sheriff blotters, and contemporaneous news reports. The California Highway Patrol’s Traffic Accident Data portal is highlighted here because it consolidates official entries that are often scattered in yearbooks or newspaper microfilm. If a notable incident did occur, its footprint would likely appear in those archives. A lack of such footprint does not prove nonexistence in any metaphysical sense, but it signals that the claim may rest more on recollection than on verifiable records.

Memory is not the enemy of evidence; it is a different kind of evidence. Stories spread through forums, comments, and retellings can acquire a veneer of inevitability. But unless primary sources corroborate, the claim should be treated as a subject for archival verification. Plausible alternatives exist: a misdated event in a neighboring county, a flood or weather event that damaged a road at other times, or a separate incident misremembered as Placer County. The burden of proof shifts toward finding a documented anchor, not toward repeating the legend.

The historian’s practice here is layered: seek official records; seek contemporaneous reporting; seek institutional memory through interviews or memoirs if available. When none of these layers yields a positive match for the specific date, the cautious conclusion is not “proven false” but “not substantiated by the public record to date.” This reframing preserves memory’s value while anchoring it in verifiable documentation.

For those who wish to pursue the topic further, the CHP data portal and other official resources offer a framework for understanding how data and memory intersect in transportation history. See the CHP data portal for official accident data and the context it provides for understanding transportation risk and history (external resource). https://www.chp.ca.gov/traffic-data

On the Edge of Regulation: Off-Road Safety in 1968 and the Placer County River Question

A rumor or a date can travel far before any verifiable record catches up with it. May 13, 1968, in Placer County, is one such name that has surfaced in conversations about historical incidents, and the image of a truck off the road and into a river captures a dramatic moment that begs for context. In the absence of a confirmed archival entry, this chapter does not pretend to reconstruct a precise event. Instead, it uses that prompt as a doorway to examine how safety rules, technical expectations, and the environmental realities of off-road work and recreation in 1968 intersected. The aim is to illuminate the regulatory landscape that would shape any truck negotiating rough terrain near water—how drivers were instructed to behave, what equipment could be required or expected, and how governments divided responsibility between road safety conventions and locally crafted standards. In doing so, the discussion moves beyond a single moment to reveal the kind of questions historians and researchers must ask when a date appears but corroborating records do not stand behind it. A careful approach recognizes that a story might be more instructive in what it suggests about a period than in what it records about a specific day.

The frame for this inquiry rests on the safety regime surrounding 1968, especially the conventions and norms that guided how vehicles were designed, operated, and protected on the public road, and how those same ideas crossed into off-road work and leisure in different national settings. The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) oversight of road traffic in that era produced a milestone: a global shift toward standardized safety features for on-road vehicles, aimed at reducing driver injury and improving passenger protection. The 1968 Convention on Road Traffic, often cited as a foundational reference, underscored the universal impulse to limit risk through technical and behavioral measures. Yet, even a quick reading of the convention reveals a crucial caveat: its provisions primarily address vehicles operating on public roads. The explicit focus on seat belts as a mandatory comfort for drivers and passengers marks a turning point in road safety, but it does not automatically translate into a one-size-fits-all mandate for off-road trucks that operate outside the Pavement.

This divergence between on-road regulation and off-road reality mattered in concrete terms. A truck venturing onto a river’s edge or wading through a shallow stream would rely on drivers and operators to interpret safety within a local framework, because the convention’s belt-and-structure logic did not specify how to handle mud, erosion, flash floods, or the hazards of water risk to a vehicle designed for rough terrain rather than for highway endurance. In such environments, national and local regulations—if they existed in a formal sense—would determine what equipment had to be on board, what protective gear was expected, and what rules governed the use of seat belts, helmets, or other protective devices. To understand what might have guided a Placer County scenario in 1968, one must therefore travel through the difference between international road-safety language and the everyday safety practices adopted by operators in diverse settings. The absence of a uniform off-road standard did not signal lawlessness; it reflected a reality in which responsibility often rested with the operator, the employer, or the local authority that supervised the terrain or the task at hand. This is not a critique of lack of regulation, but a recognition that the 1960s world of off-road operation existed in a space where national traditions, weather, terrain, and economic pressures sculpted safety in ways that no single treaty could fully anticipate.

In 1968, off-road activity spanned a broad spectrum: agricultural tasks, logging and forestry work, mining operations, and countless recreational ventures that pushed vehicles into uneven landscapes. The safety discourse in this milieu tended to emphasize practical protective measures and the readiness of a crew to respond to emergencies rather than a uniform catalog of mandatory equipment. Where the on-road convention pressed for seat belts, off-road practice often leaned on a more holistic approach to risk that could include personal protective equipment for riders, such as helmets in contexts where heads and necks faced greater exposure. The literature from the period hints at a mosaic of expectations: in some settings, safety gear for operators who worked in exposed conditions became a default; in others, it remained the responsibility of training and workplace culture. The use of protective clothing, sturdy boots, and gloves reflects a broader incremental development of occupational safety culture that was spreading across industries. The absence of a universal rule for off-road vehicles did not imply that safety was arbitrary. It signaled that safety depended on the interplay of vehicle design, operator skill, environmental awareness, and the capacity of local authorities to enforce or encourage prudent practices.

What about the vehicles themselves? In the late 1960s, the technology of off-road operation included robust chassis, flexible suspensions, and drivetrain layouts designed for traction over irregular surfaces. A truck used in rugged terrain might feature a drivetrain capable of gripping uneven ground, a frame sturdy enough to resist twisting under load, and tires meant to bite into soil and rock rather than yield to pavement wear. Yet, the same projects or tasks that required such durability also introduced vulnerabilities. In mud and near water, for example, a vehicle’s traction and buoyancy could be compromised, and a sudden slip toward a riverbank could become a life-threatening event for a driver and any passengers. The regulatory conversation surrounding such scenarios would be less about a specific piece of equipment and more about how operators, supervisors, and rescuers prepared for the risk. It was common in many jurisdictions for safety programs to emphasize the situational awareness of the operator, the maintenance readiness of the vehicle, and the presence of contingency plans for evacuation or rescue. In that sense, the 1968 period marks a transition from relying solely on the power of a machine to managing the risk of enacting work in challenging environments.

Nevertheless, the historical record remains fragmentary. A single date, a single vehicle, and a single river can prompt fascination, but without corroborating documents the encounter remains speculative. And yet, the strategy of looking at the period through the lens of safety frameworks yields a more meaningful takeaway: the way societies understood risk in off-road contexts in 1968 was not simply a matter of statutes and codified rules. It was a social practice. It combined international norms about road safety with national adaptations to local hazards, and it relied on the judgment of operators who learned to balance efficiency with caution. The potential Placer County narrative—whether or not the incident occurred—provides a case study in how those layers interacted. A driver, faced with uneven ground and the proximity of water, would be expected to weigh the likelihood of vehicle damage, personal injury, and environmental impact. If a belt was available and worn, it would reflect one layer of protective habit; if not, it would reveal a different reliance on field techniques and immediate risk management. In that sense, the historical question extends beyond whether a particular truck slid into a river. It probes how people and systems in 1968 imagined the problem of safety under conditions of uncertainty and challenge.

To connect this historical thread to a practical gaze on maintenance and operation, consider how the knowledge of mechanical resilience and failure modes could influence decisions in off-road contexts. A chapter on 1968 safety planning would not stop at policy; it would invite readers to reflect on the everyday engineering and craft of keeping a rugged machine functional when terrain tests the limits. The maintenance culture of the period, though not as formally codified as today, bore a kinship to modern practices that prioritize pre-use inspection, timely lubrication, and a respect for wear that could precipitate a dangerous moment in rough terrain. In this sense, the historical takeaway aligns with a more durable, problem-aware mindset rather than a strict checklist of rules. A deeper exploration of how such attitudes developed helps explain why operators in later years embraced more standardized protective devices and safer operating procedures, even as the core challenge of moving heavy loads through unpredictable landscapes persisted.

For readers seeking a practical orientation that bridges historical inquiry with hands-on craft, a useful parallel emerges. The subject of diesel mechanics and its role in reliability offers a concrete pathway to understand how maintenance and risk intersect in off-road work. The topic invites readers to think about how a robust engine, a sound cooling system, and dependable ignition can reduce the likelihood of a breakdown that leaves a vehicle stranded near a river or in a flood-prone area. It also underscores how a well-maintained truck can be a safer tool, even when the surrounding environment is harsh and unpredictable. This dimension of historical inquiry—linking safety doctrine with mechanical reliability—helps readers appreciate why some off-road operations emphasized technical competence as part of safety culture. For a practical exploration of these ideas, see Mastering diesel mechanics.

In tying the historical fabric to contemporary concerns, it is worth noting that the off-road safety conversation of the era was not monolithic. Different countries and regions codified different expectations for protective gear and for the use of safety devices. The general trend, however, was toward recognizing risk as an integral part of off-road work and seeking ways to mitigate it through a combination of equipment, training, and prudent decision-making. The on-road emphasis on seat belts, as highlighted by the UNECE convention, acted as a catalyst for a broader reflection on occupant protection in all vehicle contexts. Although off-road vehicles were not subject to the same prescriptive rules, the logic of protecting lives—through belts, helmets, or robust operator training—was becoming a shared horizon. The practical implication of this historical moment is clear: even when regulation is not uniform, a culture of caution can emerge from the interplay of international norms and local practice, guiding the conduct of drivers, supervisors, and rescuers when terrain pushes a truck toward the river’s edge.

If the Placer County moment did leave a trace in public memory, it did so not solely as a single accident but as a cue to consider how safety expectations traveled across borders and terrains. A historian’s approach would seek corroboration in multiple sources—the minutes of transportation authorities, contemporary newspaper reports, accident records, and maintenance logs—to reconstruct not just what happened, but how people understood the risk of leaving a road for a river. The absence of a clear, corroborated entry on that exact date invites humility about the limits of archival recovery. It also underscores the enduring value of the broader question: how did 1968 safety thinking shape the design, operation, and maintenance of off-road vehicles? The answer lies not in one incident alone but in the cumulative patterns of policy, practice, and professional judgment that informed every route where a heavy truck met rough ground and water.

External reference: https://www.unece.org/trans/main/wp29/wp29wgs/wp29gen/wp29gen03/1968conventiononroadtraffic.pdf

Rivers in the Rain: Weather, Roads, and the Unconfirmed 1968 Placer County Truck Incident

Rivers in the Rain opens a window on a landscape where weather does not merely decorate a day but actively tests the sturdiness of trucks, drivers, and the routes they trust. In the absence of a confirmable, well-documented event on May 13, 1968, in Placer County, memory becomes a kind of weather vane itself—tilting toward caution, curiosity, and the stubborn belief that the landscape holds stories worth tracing. The era’s roads were less forgiving than today’s modern interstates. They threaded through foothills and river valleys, where fog pooled like pale curtains in the mornings and sudden storms could drown the clarity of a fading line on an old map. If a truck ever slid toward a river on a rain-darkened road in that place and time, it would not have stood alone. It would have shared its risk with the weather, the engineering of the machine, and the decision-making of a driver trying to read the road through a spray of curtain rain and memory.

To understand the potential for such an incident, we must first sketch the setting. Placer County sits along the edge of the Sierra Nevada foothills, a region where highways followed the natural geometry of streams and canyons. In the mid–twentieth century, many routes were two-lane ribbons, carved into hillside terrain, with bridges that sometimes seemed more like careful afterthoughts than permanent fixtures. The climate in this part of California carries a dual character. Winters bring cold air and heavy precipitation, often in the form of rain that can quickly turn to slush on grade and in shaded nooks. Spring snowmelt and storm trains push runoff toward rivers that shoulder into the landscape, and summer, while drier, can still surprise with flash storms that surge across a valley floor with little warning. It is a climate of abrupt transitions, where the weather can reshape a road’s risk profile within hours, not days.

In those years, a truck’s safety depended on a fragile balance among several factors: the condition of the tires, the integrity of the brakes, the distribution of load, and the driver’s ability to anticipate where water and weather would reconfigure the surface under a vehicle. Consider the mechanical realities of the time. Trailers and tractors wore springs and drums designed for robust work, yet braking systems required careful attention; air brakes were common, but their performance could degrade in damp air or under heavy load. Without today’s sensor-driven aids, drivers read the road in real time—looking for signs of slick pavement, listening for the hiss of rain on steel, and feeling the vehicle respond to faint changes in steering input. The human factor loomed large. A slight misjudgment about stopping distance on a rain-soaked grade or a cautious choice about a crossing with uncertain footing could transform a routine delivery into a crisis, particularly when a river or a floodplain lay just beyond the shoulder.

Weather, then, was not an outside nuisance but a proximate actor. Water reduces tire friction, oils on pavement can slick a lane, and even a shallow river crossing can become an unpredictable obstacle if the stream’s edge has eroded the roadway or if debris has settled into the approach. For a truck negotiating a riverine route in the late 1960s, the margin between a controlled arrival and an off-road excursion could vanish with the drop of a cloud and the turning of a wheel. The interplay of rain, temperature, and surface texture created a dynamic environment. In many rural corridors, drainage ditches and culverts were practical, not picturesque. They could redirect a flood or, if overwhelmed, deposit water onto the surface with the force of a river in miniature. Each of these factors weighed on the driver’s decisions as a storm advanced or receded.

The archival question—the central thread of this chapter—centers on how such events become legible to later readers. The historical record is a mosaic of official logs, accident reports, and local newspaper clippings, each fragment offering a different vantage point. In 1968, the capability to capture weather data at a granular, real-time level did not mirror today’s networks. Weather forecasts relied on limited instrumentation, with sparse communication between weather stations and the highway patrol or dispatch offices. Road conditions were communicated through radio messages, not satellites, and the absence of instantaneous, nationwide data meant that a single day could yield multiple, divergent narratives about the same stretch of road. When a river or flood is involved, the challenge multiplies. A county clerk’s file may note a reported incident of a truck leaving the pavement, but unless the driver survived and described the scene, the precise weather conditions, the road state, and the driver’s decisions might lie hidden in memory or misfiled under a broader category of “accidents.” In this sense, weather acts as a lens that can both reveal and obscure.

The absence of a verifiable record for May 13, 1968, in Placer County does not erase the possibility that weather shaped that day’s events in meaningful ways. It simply underscores the limitations of archival recuperation in a period before digital searchability and before standardized incident taxonomies. The detective work of history becomes a patient process of triangulation: cross-referencing county archives, sheriff logs, state highway patrol records, and the pages of local papers that printed the same weather report in slightly different colors as the storm hammered along the foothills. If such a truck incident did occur, its trace would likely be found in a confluence of small signs—a clipped clipping here, a blotched report from the highway division there, a sentence buried in a weather bulletin that mentions a road closure near a river crossing. And even if no single, decisive document survives, the pattern the materials reveal can still illuminate the broader impact of weather on road safety.

The reality of the era’s weather-access to road safety data helps explain why such an event, if it happened, might circulate as a local memory or a note in a family scrapbook rather than as a widely reported catastrophe. People knew the Donner-like risk of a washout in a particular season, or the hazard of driving through a floodplain at dusk after a long shift. A driver who had to navigate a rainchanging landscape with the river running higher than normal would remember the decision-making moment long after the vehicle and the road had cooled in memory. In this sense, the story of a single truck potentially plunging toward a river on a spring day becomes a case study in how weather and infrastructure interact with human judgment. It invites readers to reflect on how communities learned to adapt, what precautions became embedded in routine practice, and what gaps in safety culture persisted when the weather turned uncertain.

From a maintenance perspective, the era’s emphasis on practical know-how mattered as much as formal training. A driver’s daily routine included visual checks of tires, brakes, steering, and lights; a mechanic’s work bench offered a place to inspect the linkage and the air system that kept a heavy vehicle in motion. The reference point for any discussion of risk is the engine and its ability to perform when challenged by heavy rain or cold starts in a mountain climate. In this sense, the chapter calls attention to the value of foundational mechanical literacy—an understanding of how a diesel engine breathes and burns fuel, how a transmission transmits torque, how a braking system modulates stopping power under load. The internal practice of hands-on maintenance and problem-solving reduces the likelihood that weather-induced faults become catastrophic. The related skill of reading the road, taught through experience and reinforced by routine checks, remains the quiet counterweight to the randomness of a storm.

To anchor this discussion in the kind of practical, ongoing learning that shaped a safer trucking culture, consider the idea of continuous improvement through fundamentals. A driver who invests time in mastering diesel mechanics—the kind of knowledge that allows one to identify a slipping belt, a failing glow plug, or a weary air compressor before a trip—gains a buffer against the suddenities of weather. The chapter’s embedded link to a resource that emphasizes the step-by-step path to diesel mastery is more than a footnote; it represents a throughline from 1968’s open-road challenges to a modern practice of proactive maintenance. The road, after all, does not get safer by accident. It becomes safer when technicians and drivers cultivate a shared vocabulary for diagnosing and addressing the mechanical and perceptual factors that weather can amplify.

Even as we acknowledge the unconfirmed status of a particular incident, we can still draw insights from the broader inquiry: weather matters for road safety; rural and semi-rural roads are vulnerable to the same forces that shaped every storm season; and the human and mechanical responses to weather define how safely a truck negotiates a crossing near a river. When memory meets archival evidence, the result is not a single, definitive narrative but a spectrum of plausible scenarios. The spectrum helps explain why a community may have believed a truck fell into a river on that spring day, even in the absence of a single corroborating report. It also underlines the importance of a careful, methodical approach to historical inquiry: acknowledge uncertainty, triangulate sources, and respect the complexity of weather in shaping road safety over time.

In the end, the unconfirmed May 13, 1968 event becomes a narrative device that illuminates a broader truth. Weather is not just a weather report; it is a force that interacts with road engineering, with the work routines of drivers, and with the maintenance habits that keep heavy transportation moving. The mountains and rivers of Placer County are not merely backdrops for a historical footnote; they are active participants in a story about risk, adaptation, and learning. The absence of a decisive, published record invites a more nuanced engagement with the past: the past that taught a generation of truckers to respect the weather, to trust their pre-trip checks, and to navigate the road with a discipline born from repeated encounters with rain, mud, and water. And it fosters a broader appreciation for how historical memory can guide present-day practices, even when the exact event remains elusive.

For readers who want to connect this historical thread to practical, today-relevant knowledge, one can turn to sources that emphasize the continuous, hands-on nature of road-safety maintenance. The craft of keeping heavy vehicles sound under the stress of winter storms and spring floods remains a living tradition. A driver who understands the basics of diesel power, air-brake behavior, and tire performance will be better equipped to read the road in the moment and to recognize when a route is no longer safe for a given load. The same instinct serves as a reminder that archival curiosity and practical know-how are not opposed sets of skills but complementary approaches to understanding how weather and roads shape safety across decades. By bridging historical inquiry with hands-on maintenance literacy, the narrative of the 1968 Placer County landscape becomes a resource for safer travel today.

External context can also sharpen our sense of what weather-driven risk looked like then and how it has evolved since. For a broader perspective on weather’s influence on road safety, see the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s road-safety resources, which offer a contemporary frame for understanding how policy, infrastructure, and training intersect with weather-driven risk in modern fleets. https://www.nhtsa.gov/road-safety

Rumors, Rivers, and Rescue: Reconstructing Placer County’s Off-Road Crashes and the Memory of a 1968 Tale

In Placer County, where foothill brush gives way to granite and rivers thread between granite shelves, the terrain has always tested more than a driver’s nerve. It tests the systems that stand between danger and help. The historical record surrounding a supposed incident on May 13, 1968—when a truck would have plunged from riverbank to water, if such an event occurred at all—offers a front-row seat to how memory, geography, and emergency response intermingle. The historical fog surrounding that specific date invites a broader look at how Placer County has learned to respond to off-road incidents across decades. The cautionary note in the archival record—that the 1968 event cannot be confirmed in public sources—does not diminish the relevance of the question: how have first responders, communities, and investigative efforts evolved as off-road activity moved deeper into rural spaces and more distant backcountry? The chapter that follows treats memory not as a fixed, static archive but as a living force that shapes policy, training, and readiness. It traces a trajectory from uncertain whispers of the river to a present-day framework of emergency coordination, equipment, and communication designed to keep people safe wherever wheels meet earth and water meet air in these remote corners of the county.

Placer County’s geography has always demanded a layered response. The unincorporated stretches that spread between towns like Auburn, Colfax, and the river corridors are home to forested plateaus, steep canyons, and winding dirt roads that disappear into sage and pine. When a vehicle goes off-road in this landscape, the immediate challenge is access. The first moments after a crash are defined by reach and the ability to communicate. In the past, rough terrain could delay help, turning a basic injury into a more complex rescue operation. Modern response sequences, by contrast, are built on years of practice in traversing these same slopes and banks with more precise logistics. At their core, they are about turning a potential tragedy into a solvable problem. The careful choreography begins the moment a report comes in, travels through dispatch, and lands in the hands of responders who carry with them not only medical expertise but a keen sense of place—the way a hillside echoes the sounds of a distant engine, how a creek road might be slick after a storm, or where a draw in the land offers the only possible path for an all-terrain vehicle to reach a patient.

The incident narrative that emerges from recent and documented cases provides a baseline for understanding how the county builds resilience against off-road risks. One tragedy that has shaped public memory is the loss of a young life in an off-road crash involving a youth and a family vehicle in rural Placer County. This incident, reported in local coverage, underscores the vulnerability of youth engaged in off-road activity and the responsibilities of guardians, organizers of events, and the wider community to create safer environments. It also illustrates the essential role of rapid medical intervention, interagency collaboration, and the use of specialized resources to navigate wrecked terrain, crowd control on rural roadways, and the precarious balance between risky recreation and public safety. Those lessons reverberate through every level of the emergency response chain—from the dispatch room to the field and back to the health system that treats injuries.

In this sense, the historical inquiry into a 1968 moment is less about reconstructing a single event than about tracing how the county’s emergency response culture has grown around uncertainty. When archival gaps appear, responders must rely on a robust, repeatable framework. That framework begins with rapid deployment, because time is the difference between extraction and deterioration. It relies on the intimate knowledge responders develop about the terrain—the way a dirt grade can suddenly transition into a slick clay wash after a storm, or how a river bend can alter its course enough to require an improvised crossing—knowledge that is passed down through training, practice, and shared experiences. The frontier of off-road emergencies is a moving target; it shifts with weather patterns, seasonal closures, and evolving recreational use. Yet even as the county’s landscapes evolve, the core principles of an effective response stay constant: access, coordination, equipment, and communication.

Access, first of all, is a function of terrain and timing. The terrain in Placer County is not forgiving in the manner of an urban street; it is forgiving only in the sense that responders learn the language of its ridges, gullies, and riverbanks. When a vehicle leaves a dirt road, the initial priority is to determine the safest, quickest route to the patient. That often means a multi-agency effort that couples the sheriff’s patrol with fire and rescue units and, when needed, specialized teams trained to operate in rugged environments. The collective experience of these responders—firefighters, paramedics, search-and-rescue volunteers, and deputies—builds a capability to reach people who are not only injured but sometimes inaccessible through conventional road networks. The Unincorporated areas of Placer County, with their limited street grids and sparse infrastructure, demand this kind of adaptive response, where every mile of travel becomes a problem-solving exercise as much as a rescue operation.

Coordination among agencies emerges as the most visible evidence of a mature emergency response culture. The sheriff’s department, CAL FIRE, and local fire districts cultivate joint procedures that allow them to stage assets in anticipation of a call, share critical situational awareness, and allocate medical resources in ways that prevent duplication of effort. This interagency cooperation is not merely procedural; it is practical knowledge that translates into faster access to patients, better on-scene triage, and more precise decisions about when to summon aerial support or specialized extraction equipment. In the field, radios crackle with concise, purpose-driven language, and the plan for patient care is adjusted in real time as new information comes in. The goal is to minimize the time from crash to care without compromising safety for responders who themselves must navigate the risk of further injuries while providing stabilization.

Specialized equipment is another axis along which the county’s response capabilities have expanded. In challenging terrain, the default tools of urban EMS—stretchers, hoists, and standard ambulances—give way to a broader toolkit: all-terrain vehicles capable of traversing steep or uneven ground, winches that can pull a vehicle from a dangerous spot, and heavy rescue gear suited for rugged access. The use of such equipment is not a sign of escalation but a recognition that the terrain dictates the means. The presence of ATVs and other off-road support assets in the responders’ inventory ensures that even the most remote patients receive timely care. Each deployment event serves as a test case that helps departments calibrate when it is appropriate to bring in specialized teams and when to rely on on-scene improvisation with the resources at hand.

Communication protocols tie everything together. A well-oiled dispatch system, where calls are triaged, priorities set, and resources assigned with surgical precision, is the backbone of the county’s readiness. Dispatch centers in Placer County act as a hub for information: what road is blocked, which units are in proximity, what hazards might be present, and what medical support will be required at the location. The ability to communicate with field units under adverse conditions—where signal strength is inconsistent, where weather is a variable, and where partial obstructions can limit radio range—depends on redundancy and training. In practice, this means multiple channels for information, cross-checking of patient status, and contingency plans if the primary route to a location becomes untenable. The ongoing refinement of these communications, including simulations and drills, ensures preparedness even when the truth of a given incident is unclear or evolving.

The tragic case involving a young girl’s death has sharpened the county’s focus on prevention, public education, and protective policies around youth participation in off-road activities. It foregrounds the question of safety gear, supervision, and the design of safe environments for children and families who operate or spectate at off-road events. This incident—augmented by the broader body of local reporting on off-road crashes—has motivated a multi-pronged approach: reinforcing safety standards for youth participation, increasing on-site presence of trained responders at high-risk venues, and encouraging communities to adopt safer practices around backcountry recreation. It is not merely about medical response; it is about reducing the rate and severity of injuries through preventative measures and proactive planning.

In weaving together access, coordination, equipment, and communication, the county has built a durable framework that can adapt to the changing landscape of off-road activity. Yet the question of historical accuracy remains important. If a particular event in 1968 is not substantiated by archival records, that gap matters less than the enduring lesson: emergency response is an iterative process shaped by experience, weather, terrain, and human behavior. Each responder who trains to move through a canyon on an ATB, each dispatcher who rehearses a multi-unit scenario, and each volunteer who learns to read a river’s signs contributes to a resilience that outlives any single date or rumor. In that sense, the 1968 inquiry acts as a catalyst rather than a conclusion—propelling ongoing improvements in how the county prepares for and responds to off-road incidents.

There is value in tracing this lineage as a narrative rather than a mere ledger of incidents. The continuity from rumor to response reflects how communities crave a story of turning danger into help. That desire is part of the social fabric that surrounds backcountry recreation: people want to know that, if something goes wrong, a capable, coordinated system will appear with the right tools at the right moment. Documentation matters, of course, but so does practice. Drills, field exercises, and interagency tabletop scenarios all translate to fewer moments of chaos when a real emergency occurs. The county’s current posture—rapid deployment, cross-agency cooperation, the use of terrain-appropriate equipment, and robust communication—embodies a forward-looking mindset that honors the memory of past events while not being bound by them.

In the end, the question of a single date on a riverbank becomes less a historical verdict and more a reflection on organizational learning. The story of Placer County’s emergency response to off-road incidents is a story of intention: to be preemptive where possible, precise where needed, and compassionate when protection and care must meet the human need. It is a story that acknowledges the dangers of backcountry travel without surrendering the joy of exploration. It recognizes that memory—whether anchored in a confirmed incident or in a line of practice developed through years of service—serves to remind responders that they carry more than equipment: they carry a commitment to the community’s safety, no matter how rugged the ground or how rapid the river’s current. The aim, always, is to be ready, to act decisively, and to learn continuously from every encounter, so that when a call comes in from the edge of a dirt road or the brink of a river, help is not a hope but a practiced certainty.

To readers who seek a concrete blueprint for understanding how these responses are built, the path is clear. Agencies must continue to invest in cross-border training, shared protocols, and interoperable communications. They must sustain access strategies that respect both the land’s limits and the patient’s needs. They must keep equipment ready for the realities of backcountry rescue, from rough terrain to water-crossing challenges. And they must maintain a culture of learning—drawing on every available memory, whether verified or not, to refine how responders think about risk, time, and care. That culture is the true legacy of the county’s approach to off-road emergencies. It is not a static archive but a living practice that evolves as the landscape evolves, as weather shifts, and as the stories communities tell themselves get retold with the clarity of improved outcomes.

Internal link for readers seeking a practical lens on how modern dispatch and fleet coordination support these response efforts:

- Dispatch software for fleet management

External reading to contextualize how similar incidents are reported and analyzed beyond the county:

- For further context about the referenced case and related off-road incidents, see this external report: https://www.king5.com/article/news/local/placer-county-off-road-vehicle-crash/273648094-2d8c-4b3e-b9b5-85f9a9530e6d

Final thoughts

The investigation into the May 13, 1968, truck incident in Placer County reveals the complexities of historical accuracy, safety regulations, and environmental challenges in off-road driving. Understanding the discrepancies around this event not only informs us about the past but also emphasizes the ongoing need for careful regulation and response strategies in off-road adventures today. As we navigate modern terrains, let the lessons from history guide our safety measures and preparation for nature’s unpredictability.