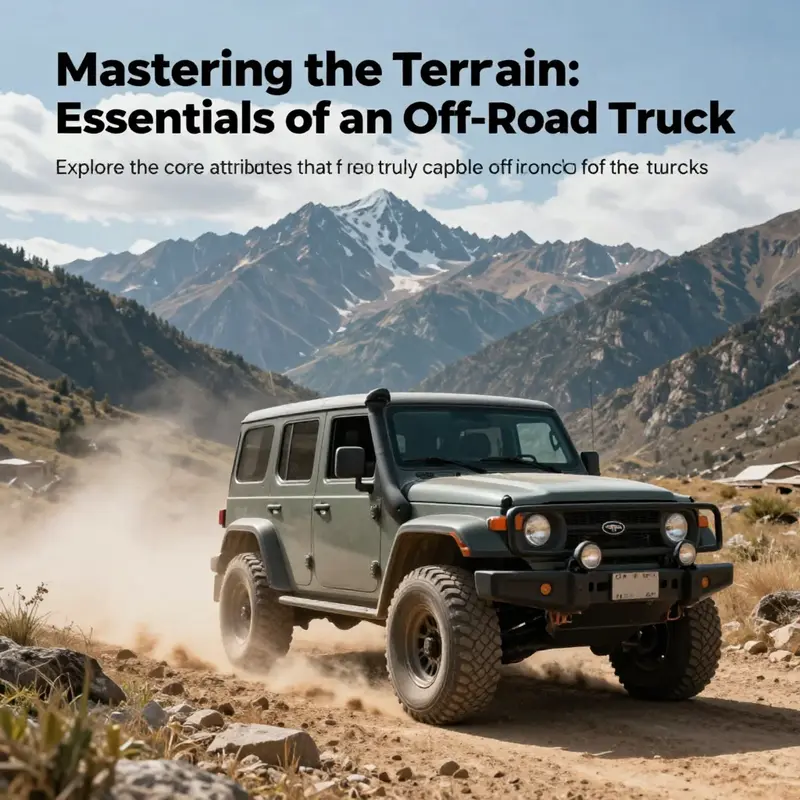

Off-roading isn’t merely a hobby; it’s a lifestyle marked by passion for adventure and a pursuit of the wild. For off-road enthusiasts, adventurers, and agricultural landowners, having the right tools for the job is crucial. Central to this are off-road trucks, engineered with unique features that enable them to tackle rugged terrain with aplomb. This examination delves into the mechanical prowess, structural integrity, and high-performance capabilities of off-road trucks, ensuring they remain top contenders in all-challenging environments. From the chassis that withstands the trials of nature to the engine power that propels them through mud and rocks, each chapter unveils the pivotal components that make an off-road truck truly great. Buckle up as we explore the elements that you need to dominate the toughest trails.

null

null

Power Under Pressure: How Drivetrain Architecture Defines a Truck’s Off-Road Prowess

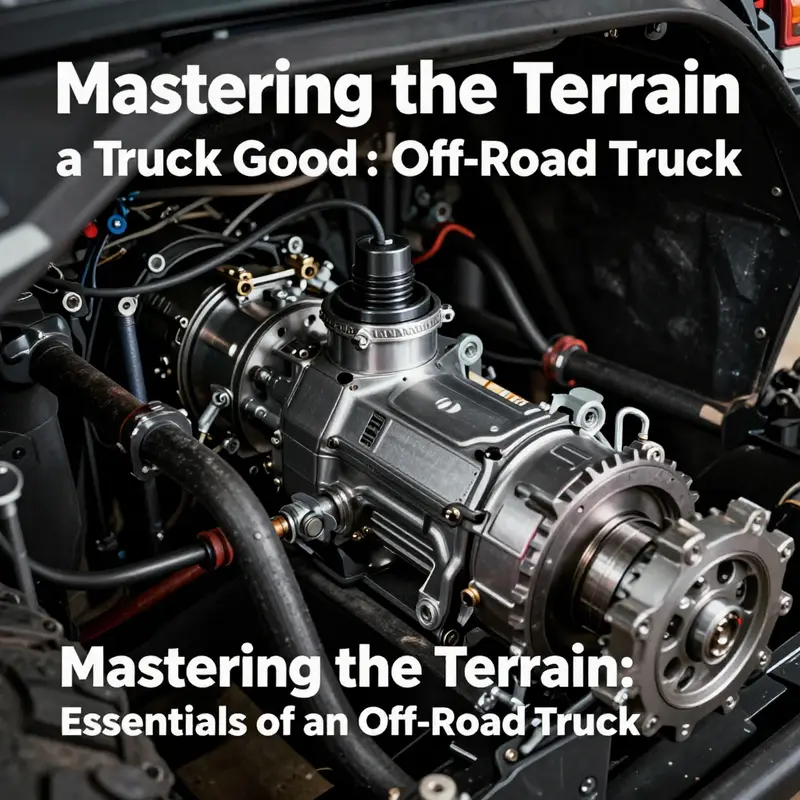

Power under pressure is not a slogan; it is the working reality of off-road travel. A truck’s drivetrain is the quiet force that transforms engine torque into traction, control, and confidence when ground falls away under the wheels. In tough, unpaved environments—mud, sand, rock, or broken terrain—the drivetrain is less about raw horsepower and more about how that power is managed, distributed, and refined at the contact patch. This is where the engine, transmission, transfer case, axles, and differentials braid together into a system that can be counted on when the going gets brutal. It is a reminder that capability on rough ground is not only a matter of more torque but of smarter delivery, deliberate gearing, and mechanical resilience that survives repeated torque washouts from obstacles and stumbles across uneven surfaces. To understand what truly makes a truck good off road, one must begin with this core: a drivetrain designed to move power to the ground with precision, repeatability, and the capacity to survive heavy use in endurance scenarios.

At the heart of the drivetrain, the engine’s role goes beyond peak horsepower. In off-road work, torque at low RPM often matters more than peak power at high RPM. A robust engine supplies usable torque right where crawl speed dwells, letting the truck press into climbs and negotiate obstacles without revving wildly. But torque is only part of the story; it must be controlled and delivered to each wheel in a way that preserves traction when surfaces betray grip. That control begins in the transmission and travels through the transfer case and axles to the wheels themselves. The transmission is not merely a box of gears; it is a sophisticated partner that, in many trucks, learns the terrain and adapts to demanding conditions. A modern off-road drivetrain uses a transfer case to split drive to the front and rear axles, and often includes a low-range gear set. This low range multiplies engine torque at low speeds, enabling crawling over large obstacles or steep vertical climbs where precise throttle application and throttle-response predictability are essential. In rough terrain, the ability to reduce speed without sacrificing pull becomes a decisive advantage. A two-speed or two-range transfer case, coupled with a carefully chosen final drive ratio, makes the difference between a truck that merely climbs and one that can pick a precise line through a boulder field.

The four-wheel drive system itself deserves close attention. A robust 4WD system is not simply about sending power to all four wheels; it is about when and how that power is shared. Part-time 4WD, which the driver engages for tough terrain, is valued for its simplicity and reliability. It allows the vehicle to behave like a traditional two-wheel drive under normal conditions, then step into a locked, all-wheel arrangement when needed. Full-time 4WD, with a low-range capability, offers constant engagement among axles, maintaining traction even as conditions change rapidly around an obstacle. In the most demanding landscapes, the true difference comes from the ability to modulate torque across wheels with a disciplined logic that reduces slip and preserves momentum where momentum is a meaningful currency. When the terrain rises into steep, slippery rock or a slick, curved approach to an obstacle, a driver needs more than raw power; they need torque to be guided through the right wheels at the right times, with the vehicle staying predictable and controllable.

Locking differentials, or diffs, are the most famous levers in the off-road toolkit for turning potential into tangible traction. Open differentials allow wheels on the same axle to rotate at different speeds, which is excellent on pavement and good on mild off-road surfaces. But when one wheel encounters a slick patch while the other still has grip, open diffs can funnel power into the slipping wheel, leaving the truck stranded. Locking differentials remedy this by mechanically connecting the wheels on an axle so they rotate together, forcing both wheels to share the same torque and enabling the truck to advance even if one wheel has little to grip. In the most capable setups, a truck employs locking mechanisms on each axle—front and rear—to maximize traction in cross-axle scenarios, with a center locking differential to align torque distribution between the two axles. This trio of locks creates a potent baseline for traction in uneven terrains, where a single wheel might retreat to a low-grip zone while the other wheels still have purchase. In practice, this means the vehicle can perform a controlled “walk” over a tangle of rocks, roots, and ruts, instead of being immobilized behind a single point of failure. The psychological and real-world effect of locking diffs is profound: it transforms a difficult obstacle into a solvable one, especially when line choice is constrained by the terrain’s geometry.

The transmission deserves its own careful discussion. Manual gearboxes offer precise, deliberate control over gear selections in tricky terrain. They enable the driver to hold a certain engine speed, maintain a predictable pedal feel, and orchestrate the torque curve with direct human feedback. In limited or technical environments, that tactile connection can be an advantage; the driver becomes a finely tuned instrument in the machine. Automatic transmissions, by contrast, bring a different kind of mastery to the table. Modern automatics with off-road modes and adaptive logic can alter shift patterns on the fly to maintain momentum and prevent torque drop during a crest or a dip. Features such as hill descent or crawl control—whether implemented through software or hydraulic logic—are designed to remove guesswork from throttle input at low speeds while the vehicle maintains a controlled descent or ascent. Transmission cooling is another critical factor in off-road duty. Prolonged crawling, water crossings, or long climbs generate heat in the torque-converting stages. Without an effective cooling strategy, gearsets and clutches can overheat and lose response. A robust drivetrain design anticipates this with refined cooling paths, thermal management strategies, and durable materials that resist heat-induced wear.

The integration between the drivetrain and other systems matters as much as the mechanical hardware itself. Electronic stability control, traction control, and hill descent devices are not mere add-ons; they interact with the mechanical backbone to shape how the truck behaves when grip is scarce. In a well-balanced setup, electronics support the driver by modulating brake force and engine output to preserve line, prevent wheel spin, and keep the vehicle from tipping or pitching on uneven ground. Yet there is a trade-off to be managed. When the terrain demands full torque to a wheel with a better grip, mechanical locks can provide guaranteed traction even as electronic systems attempt to modulate slip. A good off-road truck achieves a nuanced balance: the driver can lean on mechanical certainty from locking diffs when needed, while electronic aids supply stability and predictable response under dynamic conditions. The best systems allow the driver to choose the level of intervention and to rely on the drivetrain’s competence rather than on electronic crutches alone.

If the discussion leans toward the future, it is natural to touch on hybrid or electric drivetrains. Electric motors deliver near-instant torque across a broad bandwidth of RPM, which can translate into remarkable climbing capability and smoother slow-speed progression through rough terrain. Hybrid configurations promise the best of both worlds: strong low-end torque from electric motors combined with a robust internal combustion engine for sustained pulling power over longer distances. The universal lesson remains unchanged: the powertrain that truly performs off road is one that can deliver torque reliably, at the right time, to the wheel that currently needs it most. In practice, this means not only choosing the right gear ratios and locking strategies but also designing the system so that torque delivery remains stable as the terrain changes and as the vehicle’s suspension articulates over obstacles. The result is a truck that can maintain momentum through cross-lines, adjust to the grade of a hill, and keep all four wheels in contact with the ground as long as possible.

To connect these ideas with hands-on maintenance and a deeper understanding of engine and drivetrain behavior, a practical resource on diesel engines and mechanical performance can be helpful. For a detailed, step-by-step exploration of diesel mechanics and torque management, see Mastering Diesel Mechanics: A Step-by-Step Path to Success. This resource offers a clear bridge between theory and practice, helping readers appreciate how torque curves, cooling strategies, and component wear influence off-road performance and reliability. The link provides a grounded pathway to understanding how basic principles translate into real-world capability under demanding conditions.

In sum, the drivetrain is the nervous system of a truck when the road becomes an obstacle course. Its strength lies not in a single feature but in the interplay of a capable 4WD architecture, a low-range transfer system, locking differentials, a transmission that matches terrain to tempo, and electronic aids that keep the vehicle safe and predictable without masking the raw physics of traction. A truly capable off-road truck does not rely on one magic button or one impressive spec. It relies on a cohesive, well-proportioned system designed to deliver torque, maintain control, and preserve momentum across the most challenging landscapes. When these elements work in harmony, the truck can negotiate steep grades, slippery rock faces, and uneven trails with a calm confidence that makes difficult passages feel almost routine. The result is not merely a vehicle that can climb a hill or cross a rut; it is a machine that can adapt, respond, and endure, quietly transforming a rough track into a controlled, navigable route. And that adaptability is what ultimately separates a good off-road truck from the merely capable one.

External reference: Car and Driver: What Makes a Truck Good Off Road—Drivetrain and Transmission Systems

Riding the Rough: How Suspension Travel and Ground Clearance Define True Off-Road Capability

Riding the Rough: How Suspension Travel and Ground Clearance Define True Off-Road Capability

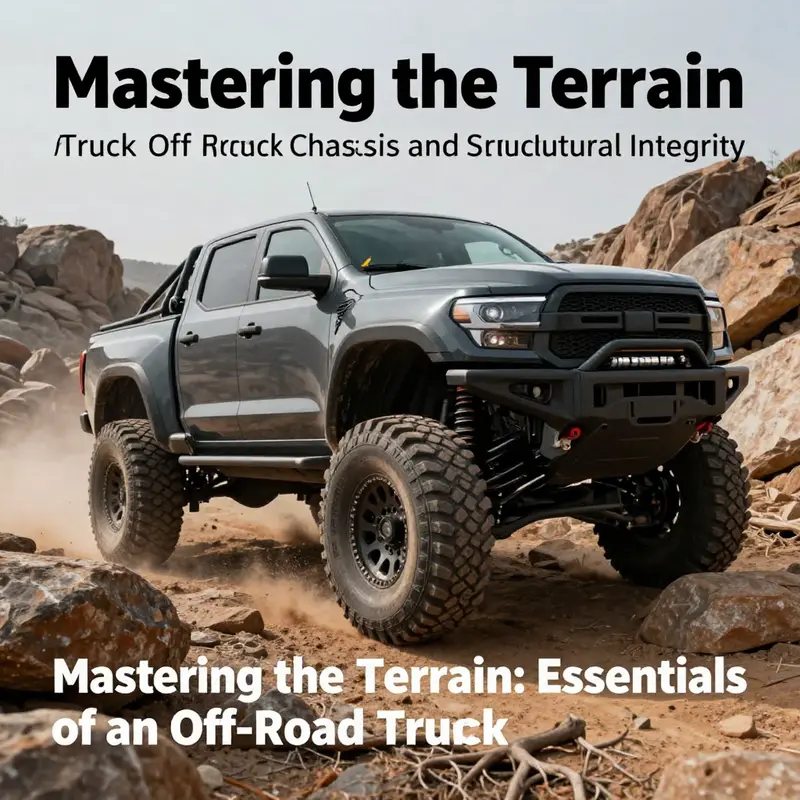

When a truck meets the unrelenting surfaces of the outdoors, the difference between a pass and a breakthrough is seldom the engine’s roar or the badge on the hood. It is, more often, the quiet physics of how the suspension soaks up shocks and how high the underbody sits above the jagged world it must traverse. Suspension and ground clearance are not flashy features; they are the interface between the driver’s intent and the terrain’s inertia. They translate torque into traction, weight into contact, and risk into maintainable control. In truthful off-road work, a truck’s ability to stay calm under pressure—its capacity to keep all four tires gripping and its undercarriage safely clear of harm—rests primarily on these two elements. The chassis, the 4WD system, and even the locking differentials support this core function, but without a thoughtfully engineered suspension and adequate clearance, traction is transient and protection is reactive, not proactive.

Suspension is the vehicle’s nervous system on rough ground. It governs how a single wheel responds to a rock, a rut, or a sudden drop, and how the neighboring wheels react to the same obstacle. A well-tuned suspension maintains tire contact with the ground, even when the terrain refuses to cooperate. That contact is the primary source of traction. If a wheel loses contact, the chance for grip drops dramatically, and the driver is forced to compensate with throttle, steering, or momentum, often at the expense of control. The opposite is equally true: when the suspension is too stiff, it can ride over terrain rather than into it, skipping from peak to trough and leaving the tire’s footprint small and inconsistent. The balance between compliance and support is the heartbeat of off-road competence.

A modern off-road truck achieves that balance through a combination of independent movement and controlled emotion. Independent suspension—whether it uses double-wishbone, multi-link, or trailing-arm configurations—allows each wheel to respond to the ground on its own axis. This independence is what keeps a tire planted on the ground when the opposite corner encounters a rock or drop. It prevents one wheel’s chop from jolting the entire chassis, which would translate into violent steering inputs and a loss of traction. Long-travel designs extend this capability further, letting the suspension articulate through large vertical motions without forcing the tire away from the ground. In practical terms, long travel means the wheel can drop into a trench, rebound, and still keep the tire in contact with the surface, maintaining grip while the vehicle remains on an even keel overall.

Solid axles, in contrast, have earned a reputation for durability and predictable behavior in rough conditions. They excel in stubborn, high-load applications where simple, robust geometry and easy maintenance matter. A solid axle system can maintain a consistent track for each wheel, which in turn preserves predictable steering and propagation of force through the drivetrain. But when a single wheel encounters a sharp obstacle, the entire axle tends to move as a unit, which can reduce independent wheel articulation. The best trucks often blend the advantages of both approaches. They use a chassis architecture and suspension tuning that preserve articulation and ride quality on the trail while still delivering straightforward reliability under heavy use. In all cases, the aim remains the same: maximize tire contact, smooth out the terrain’s asperities, and keep the truck stable enough to allow deliberate driver input.

The mechanics of articulation deserve special emphasis. Articulation is the range through which a wheel can move vertically while the rest of the suspension remains relatively level. High articulation translates into better grip on irregular ground because more wheel travel keeps at least three tires in contact with the surface, sharing the load and keeping momentum steady. A suspension system with limited travel will quickly run out of grip when confronted with a rock, a rut, or a sharp edge. The balance here is subtle: too much travel without adequate damping can lead to a wallowy feel, where the truck’s weight shifts and oscillates rather than settles, making precise control difficult. The art lies in calibrating springs, dampers, and anti-roll behavior so the truck remains stable as it pries its way over obstacles and then settles into a controlled, grounded motion.

Equally critical are dampers. Shocks and struts are not mere cushions; they are the rate devices that shape how the suspension responds to the terrain’s tempo. Adjustable dampers, or at least well-chosen damping curves, let a truck soak up a sharp impact without transferring the bounce into the cabin or into the steering wheel. Good off-road dampers dampen the harshness of rocks while still allowing quick suspension movement when the wheels drop into a groove or crest over a bump. Too soft, and the truck wallows; too stiff, and the ride becomes punishing and the tires lose grip. The artistry is in the tune: the springs support the load and set the ride height, while the dampers moderate motion so that the wheels remain in line with the ground and the driver’s steering inputs translate into predictable, linear movement.

Yet suspension does not act alone. Its effectiveness depends on the geometry of the vehicle’s undercarriage and the tires’ relationship with the ground. Ground clearance is the second pillar of the chapter’s focus, but it is not merely a measure of distance between the bottom of the chassis and the terrain. It is the culmination of suspension travel, chassis height, approach angles, breakover geometry, and departure angles. A truck with generous ground clearance can clear a rock garden without the underbelly becoming a liability. But clear space alone does not guarantee success. If the clearance is achieved at the expense of suspension articulation or if the angles are insufficient, a vehicle will still meet obstacles with the underbody scraping or a tire binding to a rock. In other words, clearance without geometry-aware articulation is not a guarantee of capability.

Approach, breakover, and departure angles provide tangible, intuitive metrics for how a truck will handle obstacles. The approach angle is the maximum angle a vehicle can approach a ramp or obstacle without the front bumper or fascia striking the ground. The breakover angle measures the point at which the vehicle’s undercarriage can pass over a crest without scraping. The departure angle repeats the logic at the rear. For a truck designed to crawl across rocky fields, rough trails, or steep grades, all three angles must be large enough to allow progressive, controlled progress without chassis contact. It is possible to design a suspension that offers excellent wheel travel while simultaneously increasing these angles through careful geometry adjustments, protective skid plates, and judicious bumper design. The result is a vehicle that can keep its momentum while avoiding the moment of contact where leverage is lost and traction deteriorates.

Ground clearance is also intimately connected to underbody protection. Skid plates, rock sliders, and other armor elements protect vital components such as the engine, transmission, differential, and fuel systems from damage as the vehicle crawls over obstacles. These protections are not cosmetic add-ons; they establish the boundaries of what the suspension can attempt. Without protection, even the most capable suspension and the largest tires can be neutered by a single, well-placed rock. Conversely, excessive armor can add weight and reduce suspension efficiency, so the best solutions are lightweight yet robust, tailored to the truck’s mission profile. The aim is to keep the vulnerable bits safe without choking the suspension’s range of motion or increasing unsprung weight, which would degrade articulation and steering feel.

In practice, the best off-road trucks integrate suspension and clearance with a chassis that can endure the punishment of rough terrain. A non-load-bearing frame, when paired with a sturdy, well-tuned suspension, a drivetrain that can place power accurately where it is needed, and locks that can be engaged when grip is scarce, creates a system that can be trusted to do difficult work. The interplay between frame rigidity, suspension travel, and ground clearance defines how a truck translates the driver’s skill into progress on a trail. This integration matters more than any single metric, because terrain rarely presents a single challenge in isolation. Rocks demand high articulation; mud demands traction and a controlled torque curve; loose gravel asks for predictable pedal response and confident damping. A truck that can handle all these simultaneously is longer on capability than any single spec would suggest.

As with any engineering challenge, durability and maintainability are essential. Independent suspension with long travel tends to deliver smoother performance and better traction in uneven terrain, but it can be complicated to service and tune. In demanding applications, simpler, robust configurations—such as well-chosen leaf-spring layouts or trailing-arm setups—offer straightforward maintenance and proven durability in harsh environments. The most capable machines often blend these approaches: they use a simple, proven foundation that can be repaired in remote locations, with modern damping and armor that allow the suspension to stay functional for extended trips away from the nearest shop. The result is a system that remains reliable when the environment demands resilience, not just peak performance.

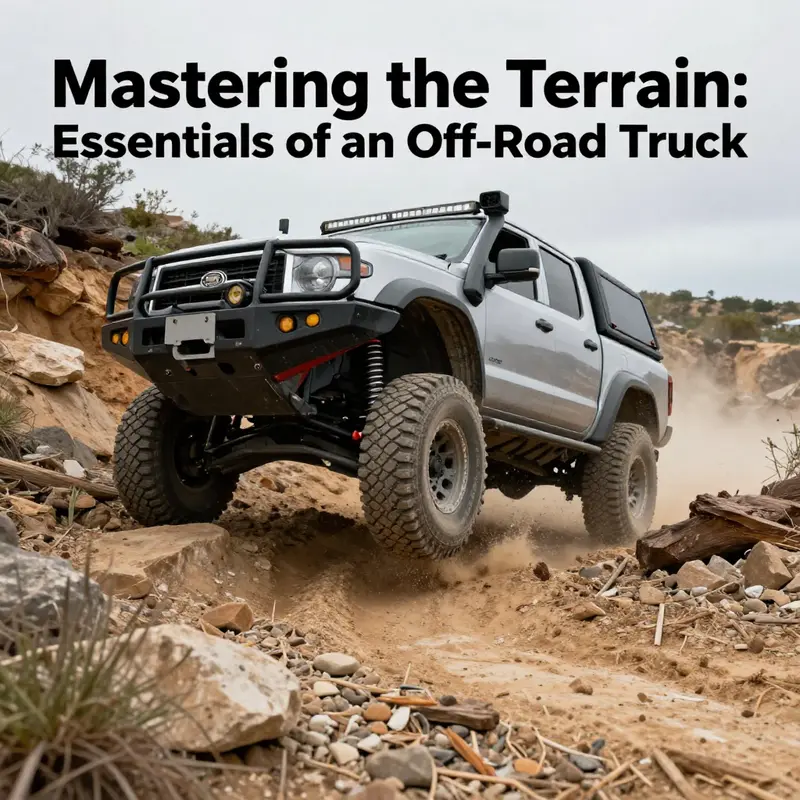

An explicit takeaway emerges from this discussion. Off-road capability is not a single feature or a shiny spec sheet line. It is a cohesive package in which suspension geometry, travel, damping, and ground clearance operate in concert with protective armor and chassis design. The driver’s ability to leverage that package—by selecting the correct approach speed, choosing the right line through a rock garden, and modulating throttle in concert with wheel travel—defines real-world capability. It is easy to overemphasize raw power or fancy locking routines, but without a suspension that can articulate gracefully and with clearance that can protect the undercarriage, the best powertrain remains a passenger on the trails.

For readers seeking a deeper, more formal dive into the mechanical fundamentals that support this narrative, a detailed exploration of diesel-driven chassis fundamentals offers valuable context. See mastering-diesel-mechanics-your-step-by-step-path-to-success for a comprehensive walk-through. While the focus there is broader, the core principles of predictable force transmission, proper balance, and robust, repair-friendly designs reinforce the ideas discussed here about how suspension and ground clearance work together to deliver credible off-road performance.

In examining the practical implications, consider how a vehicle’s suspension and clearance influence the driver’s learning curve. A truck with generous articulation and robust protection invites experimentation. The driver can test different lines on a rock shelf, observe how the tires maintain contact, listen to how the suspension smooths the transition from one obstacle to another, and adjust throttle and steering in real time. This dynamic feedback loop makes the difference between a cautious traverse and a confident, efficient pass through a difficult section. The best preparations are not about chasing the biggest tires or the strongest engine but about anticipating terrain interaction and letting the suspension do the heavy lifting of keeping the tires on the ground and the chassis away from harm.

In the broader context of the article, the emphasis on suspension travel and ground clearance aligns with the other foundational elements—body-on-frame robustness, a capable 4WD system with low-range gearing, and strategic differential locking. Together, these features define a truck that can pivot between tasks with the same calm efficiency that marks a skilled navigator. A reliably high ground clearance lets the truck take the hit of the terrain without inviting sudden contact with a critical component. A suspension that can flex, damp, and adapt keeps the tires in contact, enabling the drivetrain to deliver traction and control where it matters most. In this light, suspension and clearance become the quiet champions of off-road capability, the backstage engineers who make the visible spectacle of power and torque practical on the trail. They are the difference between a truck that can climb and a truck that can climb with confidence.

External reference for further technical context: https://www.offroad.com/technical-analysis-of-off-road-truck-suspension-and-ground-clearance-features/

null

null

Final thoughts

Understanding the foundational aspects of what makes a truck good off-road is essential for anyone seeking to harness the true potential of their vehicle. A non-load-bearing chassis, intelligent drivetrain features, advanced suspension systems, and a powerful engine work in concert to create an off-road masterpiece capable of overcoming the most demanding terrains. As you venture into nature, being armed with this knowledge ensures you can select or modify a truck that will rise to the challenge, embodying the spirit of adventure and freedom that every off-roader seeks. Whether navigating steep inclines or navigating through thick mud, the right off-road truck system is a steadfast companion in all your journeys.