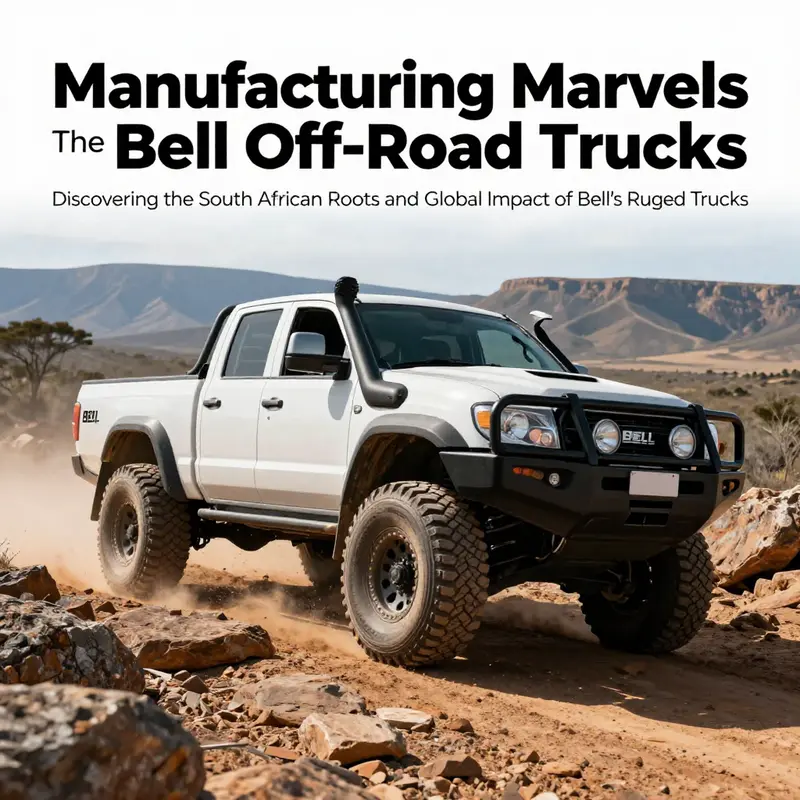

For off-road enthusiasts and adventurers, the world of heavy-duty trucks goes beyond mere vehicles; it embodies the spirit of unyielding exploration and perseverance. This article takes you back to the heart of where Bell off-road trucks are crafted—South Africa—a region known not only for its breathtaking landscapes but also for its unparalleled engineering prowess. Each chapter will delve deep into the rugged terrain of Bell Equipment’s production journey, its rich historical legacy, and the far-reaching global impacts of its mighty trucks. Buckle up as we navigate the path of innovation, passion, and resilience that defines these extraordinary machines.

Made in South Africa: Tracing the Home Ground of Bell Off Road Trucks

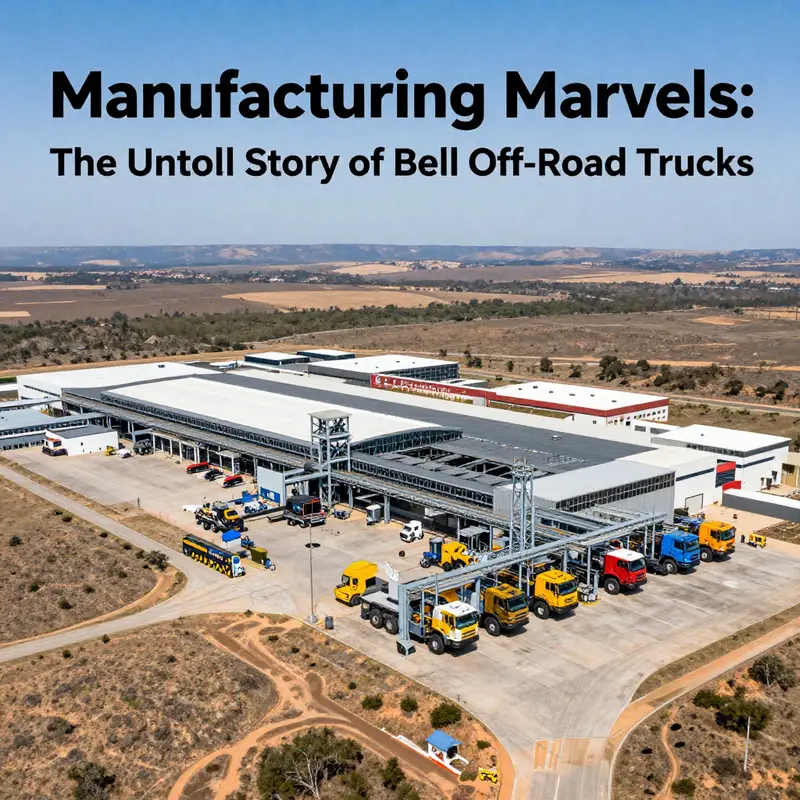

The core question of where Bell Off Road trucks are made begins with a straightforward answer, but it opens a wider view into how a nation’s industrial fabric shapes the machines that conquer the world’s roughest landscapes. Bell Off Road, a name most closely associated with heavy-duty articulated vehicles engineered for extreme terrain, roots its production in South Africa. The country is not merely a backdrop for these trucks; it is the engineering heart and the assembly line where form meets function, where rugged material meets disciplined process, and where the climate and terrain that define the trucks’ missions press the design and manufacturing teams to innovate in real time. To understand the manufacturing location is to understand the ecosystem that sustains a fleet built for dust, heat, mud, and the demanding rhythms of remote work sites. South Africa offers more than just space; it provides a dense network of skilled labor, specialized fabrication facilities, steel supply chains, casting houses, hydraulic and electrical assembly capabilities, and a logistics framework that supports both domestic use and export markets. In other words, the question of origin becomes a study in how a regional production base can align with global standards of reliability, durability, and serviceability.

From the outset, Bell Off Road’s identity is inseparable from its country of origin. The company’s headquarters and primary manufacturing footprint are in South Africa, and this alignment has grown more significant as the market for off-road heavy equipment has evolved. The rugged, all-weather, and remote-site capabilities that define Bell Off Road trucks are not accidental. They are the product of a design philosophy that prioritizes simplicity and robustness, while still balancing the needs for maintainability and serviceability in challenging environments. The South African manufacturing environment has, over years, built a culture of precision fabrication for large-scale equipment. The result is a facility floor where big components—frames, axles, beds, hydraulic systems, and cab assemblies—are brought together through disciplined assembly sequences, rigorous quality checks, and a supplier network that understands the unique demands of off-road engineering. It is a setting where engineers and technicians collaborate with suppliers who are experienced in tinting and testing components for heat resistance, dust seals, and the tolerance thresholds that keep large machines performing without excessive downtime.

A milestone in the narrative of Bell Off Road trucks is the way the South African facility interacted with industry milestones and market signals. The introduction of the B60D, a 60-tonne class machine, is often cited as a pivotal moment that framed the capabilities of these trucks within the global earthmoving spectrum. While the B60D began as a concept showcased at a major industry event—Bauma Africa in 2013—the event itself signaled more than a product launch. It signaled South Africa’s emergence as a credible hub for heavy, purpose-built off-road trucks. The concept phase fed into a production and refinement cycle that leveraged local engineering talent, existing manufacturing competencies, and a supply chain that could scale as demand grew across Africa and beyond. The outcome is not merely a vehicle but a system—a system of production that is mindful of the constraints and opportunities of the region, yet designed to meet international standards of performance, safety, and reliability.

What does it take, on the ground, to translate a concept into a field-ready machine? It begins with a strong alignment between design intent and manufacturing capability. South Africa’s industrial ecosystem provides a critical advantage in this respect. The ability to source high-tolerance components, to machine large structural elements, and to weld and assemble heavy frames with consistent quality all contribute to a manufacturing discipline that can deliver heavy off-road trucks that are both rugged and maintainable. This isn’t simply about assembling parts; it’s about ensuring that key subsystems—powertrains, hydraulics, articulation joints, and braking and steering assemblies—work in harmony under the most demanding conditions. The South African plant’s approach emphasizes modularity and compatibility across families of machines, enabling common parts and standardized maintenance procedures that reduce downtime for customers operating in remote locations.

But a manufacturing location is more than a physical site. It reflects a company’s relationship with its workforce, its suppliers, and its customers. In South Africa, Bell Off Road trucks have benefited from a workforce that understands the specialized requirements of heavy earthmoving equipment. This includes welders who can produce high-strength joints for enormous frames, machinists who can take on tight tolerances for critical components, and technicians who understand how to assemble hydraulic systems that deliver reliable power at low speeds and in extreme loads. Training, safety, and continuous improvement processes are embedded into daily work, turning what could be a rugged, ad hoc production into a predictable, quality-focused operation. A well-trained workforce translates into machines that can endure harsh operating conditions, from deserts with fine dust that penetrates seals to wet, muddy sites that demand robust sealing and corrosion resistance. The resulting product is a machine that can be trusted to perform in the environments where it will live its life—a factor that resonates deeply with customers who depend on these machines to move earth in places where downtime is not a luxury.

The manufacturing footprint in South Africa also interacts with the country’s broader industrial strategy. It serves as a regional anchor for manufacturing talent and as a node in the export network that serves multiple continents. A local footprint has advantages beyond the plant floor: faster response times for after-sales support, easier access to spare parts, and more direct feedback loops from customers who operate in diverse climates and operating conditions. Those loops feed back into product development, prompting design refinements, material improvements, and new solutions that address common real-world issues such as wear on articulation joints, cooling efficiency in hot climates, and the resilience of seals against fine African dust. The result is a dynamic, iterative process that keeps the manufacturing line aligned with the evolving needs of customers who traverse a broad spectrum of terrain—from the arid flats to the rippled terrains of remote mining sites.

To a reader looking for a precise location, the answer remains clear: Bell Off Road trucks are manufactured in South Africa, by a company rooted in that country. Yet the significance of that fact runs deeper. It reflects a commitment to local industry, to a supply chain that understands the terrain, and to a product lineage designed to endure in some of the world’s toughest environments. South Africa’s industrial base, with its specialized casting and machining capabilities, its robust fabrication shops, and its experienced labor pool, provides more than production capacity. It offers a partnership with customers who rely on these machines to perform in places where a breakdown is not a mere inconvenience but a hardship with real consequences for a project’s schedule and a site’s safety. In this sense, the location is not only geographical; it is strategic. The home ground becomes the advantage: proximity to skilled labor, a mature manufacturing ecosystem, and a culture of problem solving that translates into dependable trucks that can be maintained and repaired in the field.

The chapter’s overarching narrative also touches on how this location ties into a global context. The industrial world is increasingly influenced by global shifts toward electrification, automation, and data-driven maintenance. The trend toward electrified and more intelligent fleets has a direct bearing on where and how heavy equipment is produced. With the industry broadly moving toward higher efficiency and reduced emissions, manufacturers in established hubs like South Africa are compelled to adapt, not only to meet local regulatory environments but to position themselves for international competition. The evolution toward electrification, automation, and smarter fleet management is a global conversation, one that the industry is actively participating in. This broader arc of change is captured in external discourse on the electrification of construction equipment, a topic that resonates with the same questions that shape the manufacturing choices for Bell Off Road trucks. The ongoing dialogue about electrification, efficiency, and reliability is a reminder that the plant in South Africa sits within a larger cross-border ecosystem of ideas, innovations, and standards that define the next era of heavy equipment.

The relationship between the manufacturing base and the markets it serves is especially pronounced when considering routes to customers who operate in volatile or remote environments. The South African plant’s capability to tailor components and processes to harsh operating conditions is not a mere marketing claim; it is a consequence of a production philosophy that treats field realities as inputs to design. Engineers collaborate with procurement specialists to source materials that can withstand high wear and corrosion while keeping costs manageable. They consider how to simplify field maintenance without sacrificing safety or performance. They design for easier on-site servicing, providing modularized subassemblies that can be replaced or upgraded without reworking substantial portions of the machine. All these decisions flow from the manufacturing base’s intimate knowledge of the operating contexts that define the machines’ purpose. In essence, the plant in South Africa is not only producing a product; it is buffering the user experience against the unpredictability of the environments where the machines operate.

For readers who want a deeper, official sense of the manufacturing framework, the company’s own materials and pages offer a window into the production ethos. The manufacturing section of the official Bell Off Road site lays out the logic behind their facilities, the scope of their operations, and their commitment to quality and performance. It is a concise invitation to see how capability is built into every machine—from the initial design sketches to the final testing on the shop floor. When one surveys the plant’s capabilities in the context of its regional origin, one can appreciate how a single country can anchor a family of machines that travels far beyond its borders, built with local know-how yet designed to perform on the world stage. The South African manufacturing location is, in effect, the origin story of a family of off-road trucks whose life cycles are written in the landscapes they traverse.

This narrative also invites reflection on the nature of modern manufacturing in the heavy equipment sector. The South African plant demonstrates how a production line can balance tradition and innovation: the enduring craft of fabrication, welding, and assembly, combined with the adoption of contemporary engineering practices, testing regimes, and quality controls. It shows how a company can maintain a local presence while engaging a global market. The trucks are built to be field-friendly, but their creation is not restricted to a single geography; it is the product of a network that spans suppliers, engineers, technicians, and service professionals who share a common goal: to deliver machines that can withstand the rigors of demanding sites, operate with efficiency, and offer predictable long-term performance.

Readers who trace this manufacturing lineage will understand why the location matters not just for the truck’s identity but for the user’s experience. When a machine is made where its designers have a deep understanding of the terrain, climate, and project schedules, it becomes easier to rely on it during long shifts in remote locations. The South African production base has, over time, become a repository of practical knowledge about how to engineer, assemble, and certify heavy off-road machines so that they can face the harsh realities of their tasks without compromising safety or uptime. In this sense, the question of where these trucks are made is a question about how a region’s industrial culture shapes a machine’s performance, reliability, and serviceability. It is a reminder that where a machine is made matters, not just for the pride of origin but for the concrete, on-the-ground realities of the work it enables.

As the industry continues to evolve, with electrification, hybridization, and advanced telematics becoming more common, the South African plant’s role may also expand in response to new design requirements and market demands. The plant’s capacity to adapt—whether through upgrading manufacturing lines, integrating new supplier capabilities, or adopting new testing protocols—will influence how Bell Off Road trucks remain competitive and relevant across a spectrum of markets. The story of where they are made becomes, therefore, a story of adaptation and resilience, a narrative of how a regional manufacturing base sustains a global mission without losing sight of the unique conditions of its home ground. The chapter of South Africa’s manufacturing landscape in relation to Bell Off Road trucks offers a blueprint for other regions facing the challenge of producing heavy, purpose-built machinery for a world that keeps pushing for more reliable, durable, and capable equipment at lower total costs of ownership.

For readers seeking an authoritative face to this production origin, the official manufacturing information site provides explicit context about the company’s commitment to its production facilities, workforce, and process standards, underscoring the deliberate choice to base production in South Africa. This is not merely a statement of geography; it is a declaration about how the company intends to sustain quality, train a capable workforce, and maintain close relationships with suppliers and customers alike. The location, then, is a living component of the product’s story—a story that continues to unfold as engineering advances, market demands shift, and the needs of remote sites evolve. In that sense, the manufacturing location is not just a fact to be cited; it is a foundation for trust, a guarantee that the machines arriving on a site are born from a culture of endurance, precision, and practical problem solving that defines Bell Off Road trucks in the landscapes where they work.

External resource for readers who want to confirm and explore further the manufacturing backbone: https://www.belloffroad.com/about-us/manufacturing/

For broader industry context on how manufacturers are responding to the electrification trend in heavy equipment, see the discussion on the shift toward electrified fleets and regional adaptation of production lines in contemporary industry analyses. A representative exploration of electrification in construction equipment can be found in the article on Volvo electric construction equipment revolution. This reference helps situate Bell Off Road’s South African production within a global movement toward smarter, cleaner, and more efficient machines that still require rugged, field-proven reliability. Volvo electric construction equipment revolution.

Where Bell Off-Road Trucks Are Made: A South African Industrial Odyssey

The question of where Bell off-road trucks are made opens more than a geographic map; it reveals a system built to endure the most demanding environments. In South Africa, a country with a long history of mining and heavy industry, a manufacturing identity has grown around rugged, all-terrain machinery. The answer is not a single factory floor or a lone assembly line; it is a cohesive ecosystem where engineering, skilled labor, supplier networks, and rigorous field testing come together. In this ecosystem, Bell Equipment has cultivated a manufacturing presence that aligns with local capabilities and serves regional markets with machines designed to perform in extreme heat, dust, and rough terrain. The narrative of where these trucks are made thus becomes a story about a country that has learned to translate metal, diesel, and grit into machines capable of moving mountains and connecting remote corners of the world with durable, dependable equipment.

The roots of this manufacturing narrative stretch back to Bell Equipment’s emergence as a dedicated off-road vehicle division within a broader engineering enterprise. Beginning in the late twentieth century, the company set out to create specialized trucks capable of handling mining cycles, quarry work, and challenging civil projects across the Southern African landscape. What began as a focused development effort on purpose-built heavy-duty platforms gradually evolved into a robust manufacturing program anchored in South Africa. That origin matters because it anchored the capability to design, produce, and continuously improve machines in a region intimately familiar with the kinds of challenges these vehicles must endure. The local focus also created a talent pool steeped in metalworking, welding, hydraulics, and machine assembly, with shop floors that learned to balance precision with speed and to integrate complex systems in a harsh, real-world setting.

To understand the place of manufacture, one must look beyond the blueprint to the testing ground where theory is tempered into reliability. The off-road trucks emerging from South Africa during the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries were conceived with the harshest environments in mind: remote mining sites, unpaved access roads, heavy payloads, and the need to keep moving when weather turns against them. The engineering ethos prioritized chassis robustness, efficient powertrains, and suspension geometry that could absorb punishment without compromising control. Designers built in redundancy and modularity so that maintenance crews could address wear points quickly and keep throughput up even when supply lines faced interruption. In practice, this meant machines that are easier to service in the field, with parts that can be swapped quickly and standardized systems that technicians learn to diagnose with limited tools in remote locations. The result is a lineage of machines that members of the workforce can relate to—machines that feel part of the local landscape because their design integrates with it rather than imposes upon it.

A pivotal moment in this story was the industry-wide push to expand capacity while preserving reliability. The early concept of a 60-ton class all-weather truck emerged as a response to mining demands that favored both higher payloads and the ability to operate in varied geographies. In the context of Bell’s development arc, this milestone did not rely on flashy specifications alone; it was about translating a heavy-duty concept into a practical, repeatable manufacturing process. The design approach emphasized a two-axle configuration with a driven front axle and an independent front and rear chassis arrangement. This configuration offered better traction on uneven ground, improved load distribution, and greater stability when locomoting across challenging surfaces. The idea was not merely to push mass but to optimize how weight, torque, and geometry interact under real-world working conditions. In a sense, the two-axle concept became a symbol of Bell’s adaptation to evolving market needs: higher capacity without compromising control or reliability, even when the job site is less than forgiving.

That design logic, applied within a South African factory floor, shows how manufacturing in this region has evolved into something broader than a simple assembly operation. It is a disciplined process that blends metalworking skills, precision welding, hydraulic fitting, and mechanical assembly with rigorous quality control. Local suppliers supply components that are designed to endure heavy use and extreme environments, while the manufacturing lines are organized to minimize downtime and maximize throughput. The result is a product line that can be produced at scale while still delivering the durability that field operators expect. The South African manufacturing environment thus fosters a cycle of continuous improvement: operators provide feedback from the field, engineers refine components, and technicians implement adjustments on the line. This loop helps ensure that each truck leaving the facility is tuned not just for performance in theory but for real-world endurance.

In discussing the current status, it is essential to acknowledge that this manufacturing hub remains deeply connected to the country’s wider industrial ecosystem. The facility does not stand apart from the mining economy; rather, it is interwoven with it. Mining regions demand equipment that can keep pace with a relentless work rhythm, and the manufacturing center responds with processes that emphasize reliability, long service intervals, and predictable maintenance needs. The local workforce—comprising machinists, fitters, welders, assemblers, and maintenance technicians—brings tacit knowledge accrued through years of exposure to heavy equipment. The workforce’s experience translates into a practical intuition: machines are built to be serviced, not just operated. Training programs, on-site schools, and hands-on mentoring foster a culture where operators understand not only how to run machines but also how to preserve their longevity. This human dimension matters as much as the steel and hydraulics because it ensures that the design intent—sturdiness, resilience, and adaptability—remains intact once the equipment is deployed on distant sites.

The testing grounds for these machines extend far beyond the factory floor. South Africa’s varied climate and geography provide a natural laboratory of extremes: dusty roads, seasonal rains, corrugated surfaces, and the unyielding demands of load-bearing cycles. The trucks are evaluated in all-weather conditions to simulate the worst-case days on a mine or construction site. Engineers observe how chassis flex, suspension travel, and drivetrain responsiveness perform under fatigue, then translate those observations into refinements on the assembly line. This intimate feedback loop between field performance and factory design is what makes a manufacturing origin feel personal to operators who rely on these machines every day. It is also what helps explain why South Africa remains a credible center for heavy-truck production in Africa and beyond. The country’s proximity to mining belts, its established industrial base, and its skilled labor force converge to enable a level of manufacturing discipline that is difficult to replicate in distant markets.

Beyond the shop floor, the story of where these trucks are made intersects with a broader strategic vision. South African production supports regional supply chains that serve neighboring markets, enabling distribution networks that can respond quickly to regional demand. The emphasis on durable design and straightforward maintenance supports a service model that travels with the fleet—the kind of approach that reduces downtime and increases productive hours for operators who depend on robust equipment to keep mining and infrastructure projects moving forward. In this sense, the manufacturing origin is not just a place on a map; it is the backbone of operational reliability for customers who work in demanding environments. The regional focus helps ensure that spare parts and expertise are accessible, reducing the latency that can otherwise hamper critical projects.

As the production story has evolved, the emphasis on value has remained constant, even as technology has crept into more aspects of design and operation. The trucks are built to maximize uptime, with emphasis on simplicity and maintainability as much as raw power. The design philosophy favors modularity and standardization, which allows technicians to perform adjustments or replacements at scale without sacrificing performance. Though the specifics of individual model names are not the point here, the underlying principle is clear: a South African manufacturing program can deliver heavy-duty machines that meet diverse needs while maintaining a local footprint that underpins training, quality control, and after-sales support. This approach also translates into tangible benefits for customers who operate in regions far from centralized service centers, where local capability can make the difference between meeting a project deadline and facing costly delays.

An important facet of the internal knowledge ecosystem is access to advanced training resources and maintenance guides. Operators and technicians alike benefit from learning materials that explain how to optimize machine performance, how to diagnose issues at field sites, and how to perform routine servicing with minimal disruption to operations. A practical example of this educational dimension can be seen in the emphasis on diesel systems and mechanical endurance. The maintenance culture developed around these machines emphasizes proactive care, interval-based checks, and the use of durable consumables selected for heavy-duty cycles rather than only aiming for peak performance in ideal conditions. In this context, the idea of a transgendered, all-weather truck becomes not just a piece of equipment but a platform for reliable operation across a spectrum of climates and terrains. The objective is to ensure that every vehicle can be counted on to perform when the next blast of dust or rain arrives and to do so without requiring a significant pull-off from active work sites.

The South African manufacturing narrative also interacts with global demand in meaningful ways. While the primary focus remains on regional needs, the products reach markets that stretch across Africa and into other continents. The capacity to produce locally means that technicians can be trained within proximity to the people who will operate and service the machines, reducing downtime and increasing the likelihood that support will be timely and contextually appropriate. This geographic dynamic is not merely logistical; it is a cultural alignment between the place where the machines are conceived and the place where they are used. The result is a product lineage that carries the stamp of South Africa’s engineering ethos—an ethos rooted in resilience, practicality, and the kind of robust craftsmanship that stands up to the most demanding conditions.

In thinking about the future, one sees a continued commitment to evolving manufacturing practices. Digital tools for design optimization, simulation, and predictive maintenance are increasingly integrated into the development cycle. Even as the core principles of rugged reliability remain constant, there is room for smarter diagnostics, modular upgrades, and more efficient assembly workflows. The aim is not to chase novelty for its own sake but to build on a proven foundation with enhancements that improve uptime, reduce operating costs, and extend service life in challenging environments. The South African production network stands ready to adapt to new material science advances, evolving testing protocols, and the changing needs of customers who operate in resource-constrained settings. In other words, the narrative of where these trucks are made is not a closed chapter; it is a living dialogue between design, manufacture, and field reality that continues to shape how heavy equipment is built, supported, and deployed.

For readers seeking to deepen their understanding of the broader ecosystem that underpins Bell’s manufacturing in South Africa, a useful entry point is the company’s public-facing materials, which highlight the continuity between design intent and field performance. The content makes explicit the emphasis on durability, reliability, and operational flexibility—qualities that are central to the identity of the trucks produced there. While model names and technical specifications can be illuminating, the essential takeaway is that the production narrative is grounded in a country that has long been a backbone of the African mining and construction landscape. The combination of local expertise, a strategic supply network, and a tested design philosophy provides not only a product but a promise: equipment capable of maintaining momentum where it matters most, even when conditions push systems to the edge.

In closing this chapter’s journey through geography and fabrication, the reader is reminded that the question of where these heavy-duty machines come from has a layered answer. It is about a manufacturing hub in South Africa that embodies a blend of traditional craftsmanship and modern engineering discipline. It is about a history shaped by the mining industry’s relentless cadence and a workforce trained to translate that cadence into dependable, field-ready equipment. It is about a commitment to continuous improvement that keeps the machines relevant to changing environments and evolving performance expectations. It is also about the relationship between a manufacturer and its customers, built on a foundation of local capability and the promise of consistent, long-term support wherever those trucks may roam. For those who want a glimpse into related aspects of maintenance and mechanics, you can explore resources that delve into diesel systems and field-ready diagnostics, such as a practical guide on mastering diesel mechanics Mastering diesel mechanics. The combined thread of design, production, and support reveals a comprehensive picture of how a South African plant becomes a global source of reliable off-road traction.

External reference: https://www.belltrucks.com

South Africa’s Hidden Hub: Tracing the Quiet Center of Off‑Road Truck Manufacturing

When readers ask where bell off road trucks are made, the instinctive reply may be to search for a single factory or a brand‑name assembly line. In reality, the answer lies in a broader manufacturing ecosystem centered in South Africa, a region that has quietly built the capability to design, assemble, and sustain heavy, all‑weather trucks used in mining, construction, and extractive industries across Africa and beyond. The notion of a lone plant is attractive in narrative terms, but the truth is more instructive: a cluster of specialized facilities, skilled labor pools, regional suppliers, and a robust service network, all connected by growing export channels and a history of hands‑on engineering. This is a story not of a single logo on a gate but of a productive geography where the terrain, the climate, and the demands of heavy industry have tuned a cutting‑edge manufacturing capability over years. In this landscape, the question shifts from “where is it made?” to “how do the pieces come together, year after year, to deliver reliability in extreme conditions?”

The core of this narrative is the presence of a mature, engineering‑driven industry within South Africa that has evolved to meet the specific demands of off‑road operation. Articulated dump trucks and other heavy duty machines are not novelty items here; they are essential tools for moving ore, rock, and spoil in environments where mud, heat, or extreme cold can challenge equipment and operators alike. The South African supply chain for these machines rests on a combination of assembled platforms and locally produced components, supported by a network of regional suppliers who understand the peculiarities of Sub‑Saharan terrain. Skilled technicians, machinists, and engineers are nourished by a long tradition of mining and heavy industry. Apprenticeship programs, vocational training, and higher‑level engineering curricula reinforce a workforce that can respond quickly to design changes, field issues, and new types of componentry. The result is not merely a product line but a durable capability to iterate, service, and scale in a market that often demands rapid customization for local conditions, as well as dependable maintenance for long‑term operations.

Behind the scene of any large‑scale heavy truck program there is a pragmatic mix of design thinking and manufacturing discipline. South Africa’s ecosystem emphasizes modularity, where a base platform can be adapted for a range of payloads and operating envelopes. This approach reduces the lead time from concept to field deployment and makes it more feasible to address the idiosyncrasies of clients who work in remote sites with limited on‑site support. Rather than exporting a finished vehicle from a single plant to every corner of the continent, South African manufacturers tend to ship modular kits, complete assemblies, and fully built units as demand dictates, backed by a service network that can support distant mines or remote construction sites. The outcome is a capability that blends local assembly with global supply lines, ensuring that components such as axles, transmissions, hydraulic systems, and castings can be sourced reliably while still allowing for local adaptation and after‑sales service. This blend of local production and foreign supply is a practical response to the uncertain economics of international procurement, currency fluctuations, and the realities of commodity markets, which often dictate a need to balance cost with uptime.

A pivotal moment in shaping this manufacturing identity occurred at a major industry event in the region several years ago. The event functioned as a high‑profile platform where engineers, operators, and executives could observe and discuss the next generation of heavy earthmoving equipment. It was at that time that a 60‑ton class of articulated trucks—an archetypal benchmark for productivity in open‑pit environments—was showcased not merely as a concept but as a demonstration of what capability could be achieved within a local supply chain. The significance lay not in the exact model or design but in the proof that a regional producer could conceive, refine, and present a credible solution for demanding conditions. In this sense, the event helped to cement South Africa’s role as a manufacturing hub for these all‑weather vehicles. It highlighted the alignment of local engineering talent with the needs of a global mining economy that requires high uptime, predictable maintenance, and the resilience to perform across shifting geographies and regulatory landscapes.

Yet the story extends beyond engineering prowess. The export and service dimensions of South Africa’s heavy truck manufacturing are anchored by a logistics and port framework that supports regional distribution as well as international trade. The same coastline that handles bulk ore shipments also facilitates the export of heavy earthmoving equipment to neighboring countries and further afield. Port infrastructure, skilled logistics labor, and responsive after‑sales networks are not fringe benefits; they are essential components of the business model. These elements reduce total ownership costs for operators who must keep machines running across long shifts and extended campaigns. For clients, uptime is not a luxury but a criterion that shapes the vendor landscape, the terms of service, and the predictability of maintenance windows. The implication for the global market is that South Africa’s manufacturing centers are not isolated enclaves; they are nodes in a network that connects suppliers, operators, financiers, and service providers across Africa, the Middle East, and beyond.

From a strategic point of view, regional manufacturers in South Africa must continuously adapt to a shifting set of market incentives, regulatory frameworks, and environmental expectations. As heavy equipment moves toward greener powertrains and smarter telematics, the local ecosystem has begun to assimilate electrification concepts and digital monitoring technologies. What changes at the machine level, however, does not happen in a vacuum. It requires a cross‑functional approach—mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, software integration, and maintenance planning—worked into a single, coherent process. The push toward electrification in construction and mining is not merely a case of swapping out a diesel engine for a battery pack. It is a holistic rethinking of how heavy equipment is built, dispatched, and maintained. The broader narrative in South Africa reflects a global trend: operators demand cleaner, quieter, and more efficient machines, while manufacturers seek to preserve uptime and reduce lifecycle costs. In this climate, the local players are not isolated cottage industries; they are part of a global conversation about how heavy equipment should look, behave, and be supported in the decades to come. For those who study industrial ecosystems, the South African example illustrates how regional strength can translate into international credibility when the core competencies—engineering, quality control, and service excellence—are consistently demonstrated.

The question of a specific brand or company name in this context is less consequential than the underlying architectural truth: the region’s production story rests on a portfolio of capabilities rather than a single flag. If someone searches for a standalone “Bell” brand operating out of a single factory, they will not find a transparent trail of verifiable operations in public records. What is verifiable, instead, is a robust environment where a well‑established line of heavy vehicles is designed, assembled, and maintained within a localized supply chain. This distinction matters for buyers, researchers, and policymakers who want to understand how regional manufacturing translates into reliability, after‑sales service, and long‑term value for operators who must depend on their fleets in challenging environments. It also means recognizing that a global industry built on mobility and mineral extraction achieves its scale not solely through a single plant but through an integrated network of facilities, partners, and continuous improvement that keeps pace with evolving demands. In practical terms, this translates into a simple, testable reality: the hands that design a machine are often the same hands that repair it years later, in a remote site or at a regional service center, ensuring that uptime remains the primary currency of success.

For readers seeking to place this narrative in a broader industry context, it is helpful to acknowledge the presence of other long‑standing regional players who have established extensive networks to support mining and construction operations across Southern Africa and neighboring regions. These players sustain a range of configurations—from fully integrated platforms to modular kits capable of rapid adaptation to client needs. The result is a market where the value proposition centers on reliability, local adaptability, and a service proposition that extends beyond the sale of a machine to the ongoing health of an entire fleet. In such a landscape, a customer does not merely acquire a vehicle; they enter into a relationship that encompasses training, maintenance, spare parts availability, and the assurance that a global supply chain can back up operations wherever a site is located. This is the practical reality that explains why South Africa remains a focal point for heavy off‑road vehicle manufacturing in the region. It is not a single blockbuster plant, but a resilient, integrated system that translates engineering competence into field performance.

In examining how these dynamics are reflected in broader industry discourse, it becomes clear that electrification and data‑driven maintenance are not novelties but expansions of an existing discipline. The conversation around modernizing heavy‑equipment fleets often centers on two intertwined threads: powertrain innovation and fleet management. On the powertrain side, manufacturers and operators are experimenting with hybrid solutions and a range of energy storage options, aiming to reduce fuel costs and emissions while preserving the power density required for demanding tasks. On the data side, telematics, predictive maintenance, and remote diagnostics are enabling operators to anticipate failures, optimize maintenance windows, and maximize uptime. This convergence of mechanical engineering and information technology is not a distant future; it is the present reality in many large fleets that span the region and beyond. The South African manufacturing environment has become adept at listening to operator needs, integrating feedback into product iterations, and maintaining service structures that keep fleets productive around the clock. The net effect is a market that is not only competitive on price but also resilient in performance, able to function as a backbone for mining and infrastructure projects across continents.

For researchers and readers who want to explore how electrification is affecting heavy equipment more broadly, a useful touchpoint can be found in the ongoing discourse around construction equipment electrification and its industrial implications. This broader trend is captured in a range of technical, policy, and market analyses that echo the same themes: the need for reliable power sources, robust energy management, and comprehensive support ecosystems that span design, manufacturing, deployment, and after‑sales service. Within this frame, it is instructive to reference a widely cited discussion about electrification in construction machinery, which highlights progressive shifts in industry thinking and practical demonstrations of how digital and electrical innovations are reshaping the equipment landscape. The trajectory is not confined to one country or one brand. It is a global shift that the South African manufacturing community is actively contributing to through its regional strengths, its skilled workforce, and its persistent focus on uptime and service quality. For those who want to connect this chapter to broader industry developments, a current overview of electrification in heavy construction equipment can be explored in related industry literature and case studies, including published notes on how major equipment manufacturers are integrating electric propulsion and advanced diagnostics into their product platforms. A representative example of the direction of travel is captured in the discussion of electrification of construction equipment, which can be explored further through a reference to a recent industry analysis on electrification and modern fleet management, summarized in practitioner‑oriented outlets and technical reviews. This contextual lens helps readers see that the South African manufacturing narrative is part of a global evolution toward more intelligent, efficient, and low‑emission heavy equipment.

In this light, a practical takeaway for anyone evaluating where heavy off‑road trucks are produced is that the answer sits at the intersection of geography, capability, and market maturity. South Africa’s role is anchored in a long track record of engineering excellence, a network of suppliers prepared to support complex builds, and a proximity to mining and construction markets that demand reliable performance. The ecosystem is supported by a culture of skilled artisans and engineers who understand the operational realities of remote sites, the constraints of maintenance access, and the critical importance of uptime. The result is a manufacturing story that is less about a brand name and more about how a region builds and supports heavy equipment in ways that align with the realities of global mining and infrastructure expansion. For readers who want to explore how electrification and new equipment management practices intersect with this regional manufacturing capability, the discussion around Volvo Electric Construction Equipment Revolution provides a relevant cross‑reference. It exemplifies how the industry is moving toward integrated solutions that combine powerful, reliable hardware with digital tools to monitor, optimize, and sustain fleet performance across challenging environments.

Ultimately, the global impact of South Africa’s off‑road truck manufacturing lies not in a single export blast but in the steady, invisible legwork of design refinement, supply chain resilience, and service networks that empower operators to keep working even when the odds are tough. The region’s capability supports local demand while enabling regional exporters to meet the needs of neighboring economies and markets that rely on robust, capable equipment to support their own growth trajectories. In this sense, the question of “where are these trucks made?” yields a more complete answer: the trucks originate in a well‑informed ecosystem that blends local manufacturing with international supply chains, underpinned by a workforce trained to deliver reliability in the most demanding environments. The broader lesson is that manufacturing strength in heavy equipment is increasingly less about a single plant and more about an adaptive network—one that can respond to changing market conditions, new regulations, and the evolving expectations of operators who must push performance to the edge while maintaining strict uptime. For researchers and practitioners, understanding this shift is essential to evaluating equipment options, negotiating service contracts, and planning long‑term capital investments in regions where the ground itself seems to demand nothing less than durable, intelligent engineering. The South African example offers a concrete case study: a region that has aligned its technical talent, supplier base, and logistical capabilities to become a robust contributor to the global heavy‑duty truck landscape, even as the industry itself continues to reimagine propulsion, connectivity, and fleet optimization.

External reference for further context on market dynamics and regional expansion: https://www.faw.com.cn/en/news/2025-01-21-faw-south-africa-truck-sales-hit-new-high-in-2024.html

Final thoughts

Understanding where Bell off-road trucks are made offers a glimpse into the dedication and craftsmanship that goes into each vehicle. The intersection of rugged South African landscapes and advanced engineering creates trucks capable of conquering the toughest terrains around the globe. As we’ve seen, the history and evolution of Bell trucks exemplify not only technological advancement but also a commitment to quality and performance. Their impact stretches far beyond local manufacturing, affecting industries and communities worldwide. In exploring these impressive machines, we garner a deeper appreciation for the passion and expertise that powers the off-road adventure spirit.